Developers

The developers Opes recommends (and the ones we don't)

Who are all the developers you work with? Well, we counted them. In total there are 123 developers that we have had a relationship with over the last 3 years.

Property Investment

5 min read

Author: Andrew Nicol

Managing Director, 20+ Years' Experience Investing In Property, Author & Host

Reviewed by: Ed McKnight

Resident Economist, with a GradDipEcon and over five years at Opes Partners, is a trusted contributor to NZ Property Investor, Informed Investor, Stuff, Business Desk, and OneRoof.

Investors get spooked when they discover a piece of land might be contaminated.

After all, no-one wants a property that makes kids or pets sick playing in the backyard.

There are many properties where the council says the land “could be” contaminated, but in practice the land may be fine.

Here at Opes Partners we help investors find New Build properties. And land contamination occasionally comes up as a concern, especially in Canterbury.

In this article, you’ll learn how land gets contaminated and how you fix it.

The way we use land changes over time.

For instance, land that was once a farm may get subdivided. Then a developer builds 40 houses on the previous paddocks.

Because the land was used as a farm, there may be potential contamination.

For example, a farmer may have cut down trees and burned them.

I’ve seen another example where a farmer had dug a hole and dumped animal offal (organs) in there.

Or the farmer may have had an area of the land that was previously used to store coal.

All of these can cause land contamination.

Technically, land gets contaminated when a HAIL industry uses it (or operates near it).

HAIL stands for the Hazardous Activities and Industries List.

If a business on the HAIL list uses a piece of land, then it has the potential to be contaminated.

These industries tend to use chemicals or hazardous materials and include:

If any of these industries have been near the land you’re buying, your LIM will say “potential land contamination”.

I once owned a “potentially contaminated” property in the middle of Christchurch City. In this case, it wasn’t a previous farm; there used to be a panel beaters next door.

They use lots of chemicals, so the council put on my LIM that the land could potentially be contaminated.

So the first step is to look at your LIM report. This is the council’s official record about your property.

Now, just because your LIM report says “potential contamination” it doesn’t mean your land is contaminated.

You need to test it to be sure. If you get the land tested and it comes back below the threshold, the council will change the LIM.

You can sometimes find this information online; it depends on where you live in the country.

If you’re in Canterbury, you can use the Environment Canterbury website. In Wellington, they have the Selected Land Use Register.

Even if your land is contaminated, you may not need to do anything.

Existing properties have been bought and sold with potential contamination. They haven’t been tested and may not be fixed.

You only have to do something if you are digging up the soil. That includes developing, subdividing, or building a minor dwelling.

In these instances, you have to get the soil tested. And if you find contamination, you have to fix it.

This is why New Build investors often come across potential land contamination.

That’s because developers building houses on old paddocks often come across contamination. But it’s a problem for the developer rather than the purchaser.

So, by the time you pay for the property the developer will have fixed the contamination.

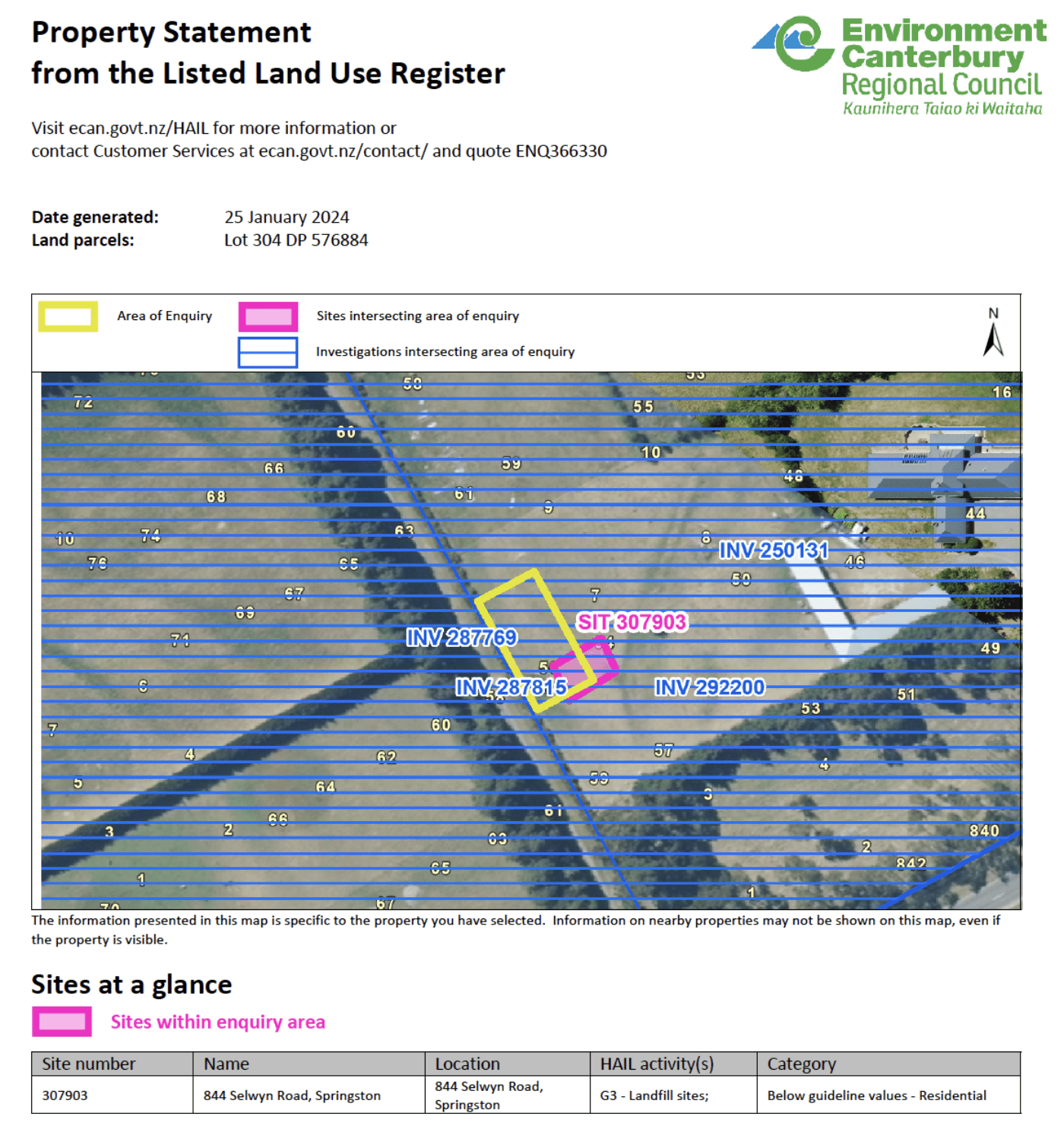

Let’s say a developer wants to build on a potentially contaminated piece of land in Canterbury.

Here’s what happens:

Step #1 – A scientist comes in and tests the soil. If there is no contamination – great. The council updates the record, and the LIM is changed.

Step #2 – If there is contamination, they have to follow a “remedial action plan” to make the land fit for purpose.

Step #3 – Dig out the contamination (in most cases) and fill in with uncontaminated soil.

Step #4 – Amend the LIM and council documents.

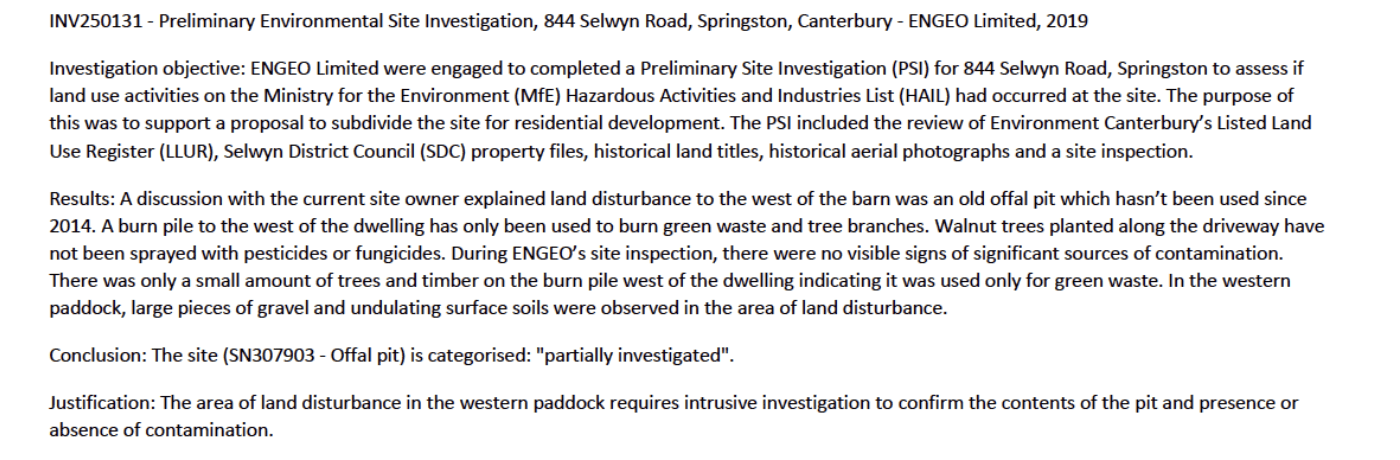

Here’s an example of a recent development site in Canterbury. Before it was developed, it had been a farm for 60 years.

Environment Canterbury (ECan) was contacted.

This development had multiple sites of “potential contamination”.

There were things like an offal pit, burn piles, an underground tank and a sheep foot bath.

The developer then came up with a “remedial action plan”. This outlined 10 contaminated areas the developer had to fix.

In one example, the developer had to dig out a 6m x 6m plot of land down to 0.75m. That’s a lot of dirt to dig out. Almost enough to fill 5 trucks.

At that point, a portable X-ray machine screened the soil to see if the contamination was still there.

It was deemed safe, and they filled the excavated site back up with new dirt.

Finally, the site was deemed “below guideline values” for a residential site. That means the land was no longer contaminated.

This meant it was safe to build on.

No, not in my experience.

In reality, people buy and sell contaminated land (and formally contaminated land) all the time. Ask a (good) lawyer and they’ll say, “This is quite common.”

This is what happened with the above case study. The investor’s lawyer reassured them that all was well and the sale went through without hiccups.

If you think about it, local councils are going to make sure any ground is fit for development purposes.

Remember, contaminated land can happen anywhere in the country (not just on farms).

If you’re buying a property that’s previously had contamination, the main questions you need to ask are:

If it’s been fixed and there is no current contamination, you don’t have to worry about it.

Managing Director, 20+ Years' Experience Investing In Property, Author & Host

Andrew Nicol, Managing Director at Opes Partners, is a seasoned financial adviser and property investment expert with 20+ years of experience. With 40 investment properties, he hosts the Property Academy Podcast, co-authored 'Wealth Plan' with Ed Mcknight, and has helped 1,894 Kiwis achieve financial security through property investment.

This article is for your general information. It’s not financial advice. See here for details about our Financial Advice Provider Disclosure. So Opes isn’t telling you what to do with your own money.

We’ve made every effort to make sure the information is accurate. But we occasionally get the odd fact wrong. Make sure you do your own research or talk to a financial adviser before making any investment decisions.

You might like to use us or another financial adviser