New Builds

Master build – Is it worth it? An honest review

An unbiased review of Master Build to see if it's a smart choice for your next project. We weigh the pros and cons, helping you decide if it's worth the investment.

Property Investment

133 min read

Author: Andrew Nicol

Managing Director, 20+ Years' Experience Investing In Property, Author & Host

Reviewed by: Ed McKnight

Resident Economist, with a GradDipEcon and over five years at Opes Partners, is a trusted contributor to NZ Property Investor, Informed Investor, Stuff, Business Desk, and OneRoof.

If you want to learn about investing in property in New Zealand - this is the guide for you.

What you are about to read is the most comprehensive, useful, and completely-free resource in the country that teaches you how to invest in property.

It is also a living article. It gets updated constantly and over time we’ll develop it even further so it’s even more comprehensive and interactive. This means adding more videos, updating calculators, including images, and deep-diving into topics.

We do this for you; this is your resource, so whenever you have a question along your investment journey you can refer back to this guide.

Do you have a question or comment about our property investment guide? Feel free to leave your thoughts in the comment section at the end of the page.

Here's a quick video from Ed, one of the guide's co-authors, introducing what you'll learn here:

When you strip out the detail, there are only two tried-and-true residential property investment strategies investors tend to use.

The strategy you choose will determine the actions you take.

The two strategies are:

The ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy involves purchasing property and holding it for the long term.

You might buy these properties and rent them out straight away. Or you might renovate the properties before renting them out.

Either way, the focus here is on holding these properties for the long term and making money as they increase in value.

The alternative strategy is ‘Buy and Flip’. This involves investing in a property that needs some work, undertaking the required renovations, and then immediately selling the property on.

The focus here is on making money through renovation activity.

Neither strategy is better than the other. They can both be used to achieve your property investment goals over the long term.

The question is: which is the right strategy for you?

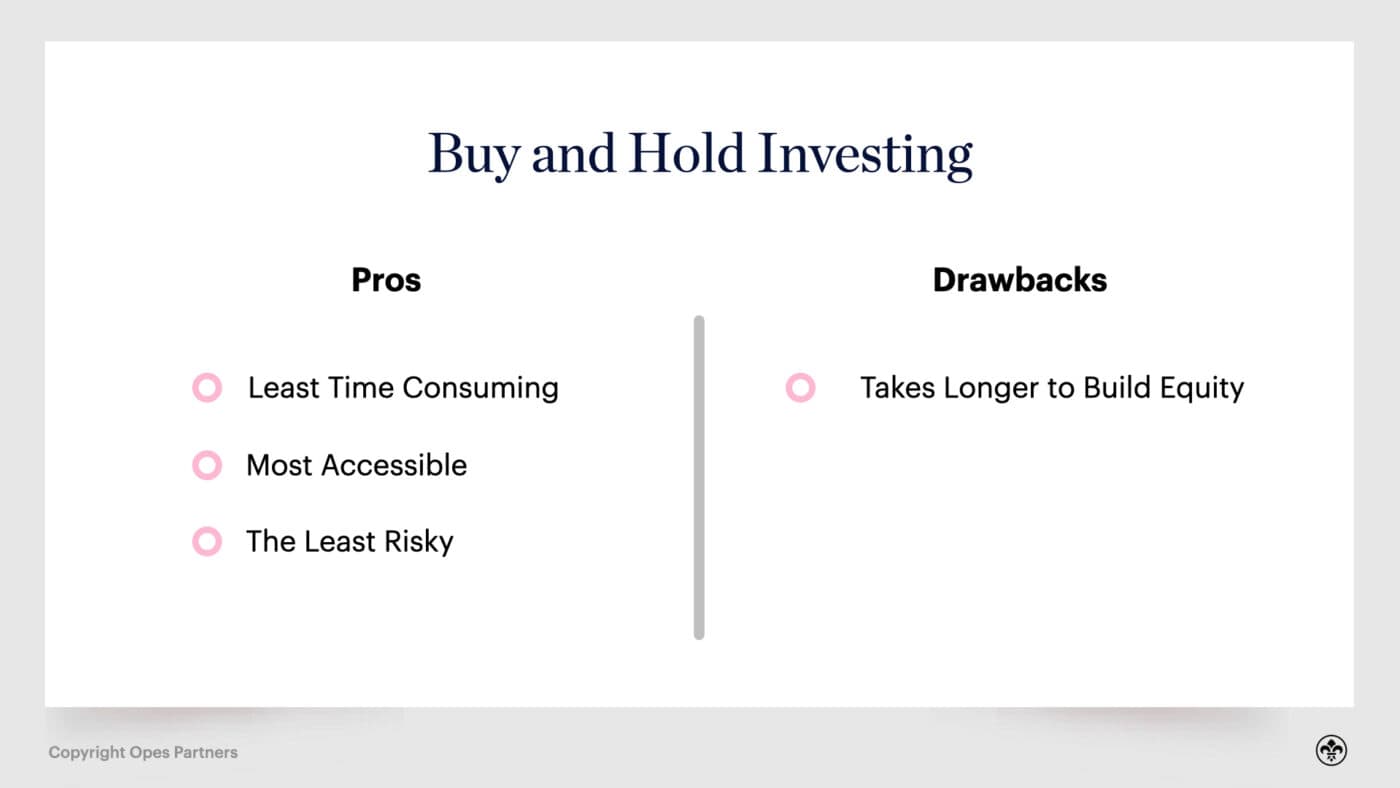

‘Buy and Hold’ is the most common strategy property investors use in New Zealand. This is for several reasons. It‘s a way to make extra money in addition to your usual income; it’s the least time intensive of the two and, while you are holding on to the property, you can still achieve that extra money through cashflow and the property increasing in value.

This strategy makes investment accessible and realistic for everyday New Zealanders who have kids, jobs and busy lives, whereas a ‘Buy and Flip ’strategy requires you to continually find new properties to do-up and sell.

In essence, the ‘Buy and Hold’ is a strategy that is achievable alongside your main job.

‘Buy and Flip’ is like taking on an extra job.

For an investor who chooses the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy, you will: purchase an investment property, (in some cases investors will renovate but not always), and then rent it out.

Once the property is rented, you will primarily make money from the property going up in value, which is a ‘set and forget’ approach.

You usually won’t do much else to the property, and renovations and maintenance are kept to a minimum.

Because of this you’ll want to find a property already in generally good condition and won’t need expensive maintenance in the foreseeable future.

For example, there isn’t an impending roof replacement or a broken hot water cylinder around the corner. These are the sorts of things that cost a lot of money and don’t increase the value of the property or rent the property can achieve.

There are three reasons investors tend to like the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy:

1. It Is The Least Time Consuming

‘Buy and Hold’ investing can be a ‘hands-off’ strategy.

If you decide to focus on properties that can be rented straight away, like New-Builds, then you can begin your property investment journey without picking up a paint brush.

Even if you decide to go down the renovations pathway, once your property is renovated, it still becomes a set-and-forget approach.

With ‘Buy and Hold’ you continue to make money for as long as you own that property. But when you flip properties, you don’t own them for very long so you need to continue buying, renovating and selling properties if you want to keep earning money.

Because the property investors who choose the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy are looking for a hands-off investment, they will often bring other professionals in to help them manage it.

At a minimum this usually includes a property manager who will look after and tenant the property for the investor (more on property managers below).

2. It Is The Most Accessible

‘Buy and Hold’ investing can also be the more accessible of the two strategies.

There are two reasons for this:

Firstly, this strategy can require the least amount of upfront money/capital to get started. Secondly, it also requires the least amount of background knowledge in the property or building sector.

How?

Let’s say a ‘Buy and Hold’ investor decides to invest in a New-Build. These types of properties only require a 20% deposit to secure bank lending.

But, for those who choose the ‘Buy and Flip’, the investor needs to purchase ‘existing’ properties, which require a 40% deposit to get bank lending. On top of that, people who ‘Buy and Flip’ need to fund their renovation costs.

To give an example, say you want to purchase a $600,000 property. If it’s a New-Build (the type some ‘Buy and Hold’ investors might purchase) then you need a 20% deposit. This means you need $120,000 to purchase the property.

But if you want to flip this property then you’ll need a 40% deposit, which is $240,000. On top of that, you’ll need to have the renovation funds, which could be $30,000 (as an example).

So, in this example, the person going with the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy needs $120k worth of deposit to get started. Compare this to the $270k for the ‘Buy and Flip’ investor.

This is why ‘Buy and Hold’ is more accessible from a financial perspective.

On the background knowledge front, to execute a ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy, at the bare minimum, you only need to know how to identify the right type of properties to purchase and where to find them. Whereas you will need to know more than that to execute a ‘Buy and Flip’.

For instance, you would need to know: The types of renovations needed to cost-effectively add to the property’s value; how to carry out those renovations; and where to source building materials.

3. It’s The Least Risky

There’s a saying in property that “time heals all mistakes”.

It’s alluding to the fact that property prices have tended to increase over time. So, even if a ‘Buy and Hold’ investor botches a purchase or a renovation, if the market increases in value, you’re less likely to lose money.

‘Buy and Flip’, on the other hand, requires you to buy and sell properties in the same market. The time between you purchasing the property, renovating it, and selling it again is often short. So, you tend not to achieve much ‘capital gain’ over that time.

Another reason ‘Buy and Hold’ investing can be considered less risky is because not all investors of this strategy choose to renovate. This means there is often less background knowledge needed to execute a ‘Buy and Hold,’ so you are less likely to mess it up, or spend money in areas that don’t make the property go up in value.

The main drawback of following a ‘Buy and Hold’ is you don’t get the money straight away.

Let’s say you renovate a property and it increases in value by $50,000. You might feel like Sir Bob Jones – NZ’s most famous property investors – and think: “I just made a ton of money.”

But that equity is often locked in the property. Yes, the property has increased in value, but it doesn’t mean you can go and spend the money.

Whereas under a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy, because you sell the property once the renovations are complete, you have the money to spend. If you want to use some of those profits on your personal living costs – that’s an option you can take.

1. Buy A Property That Is Likely To Go Up In Value Over Time

Because 'Buy and Hold’ investors primarily rely on the market to increase the value of the property over time, the investor needs to ensure the chosen property is likely to achieve capital gain.

This means investing in the right location and the right type of property, which both have growth potential.

2. Ensure You Can Hold The Property Over The Long Term

Being financially able to afford your property over the next 10+ years is essential for ‘Buy and Hold’ investors who rely on the property market to increase the value of their investment.

This is because – depending on how your property is structured financially – your investment may require you to make a cash contribution into the property’s bank account each week (i.e. the property may be negatively geared).

If that’s the case for your investment, and you can’t afford to keep the property for 10+ years, then you may be forced to sell early. This would mean missing out on the gains you wanted to achieve in the first place.

Most New Zealanders will find the ‘Buy and Hold’ is right for them. At a minimum it requires no background or specialist knowledge and can require the least amount of money to get started.

It’s also a strategy that tends to complement your day-time job, whereas a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy can easily turn into a second fulltime job.

While the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy is the path the majority of New Zealanders decide to go down, the ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy is the path many Kiwis think about going down.

This is because it is the most publicised investment strategy - just think of all the renovation shows we see on TV and enjoy watching, like The Block.

On the show couples renovate an old property, increasing its value over a few weeks and then sell the property for a profit … taking potentially tens of thousands of dollars home.

As good as the ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy looks from the comfort of our couches, we must respect and understand what it requires to be successful.

When you use a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy you’ll invest in a property that could increase in value with some building work, repairs or cosmetic upgrades.

Investors then resell the property immediately after purchasing, which is the ‘flip.’

The main difference between the two strategies:

For example, under the ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy the money you’ve made in the property is released straight away. By that we mean once you sell the property you have access to the funds rather than them being locked into the house in equity.

Also, because you’ll be less concerned about the ongoing maintenance of the house you are investing in (e.g. a roof that needs replacing in 5 years), this will affect the type of property you go looking for.

1. Immediate Equity Gain

While not all ‘Buy and Hold’ investors renovate, almost all ‘Buy and Flip’ investors will.

Successfully executed, a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy is the quickest way to create immediate capital gain (equity) within the property, because once renovations are finished the property is worth more.

With this strategy, if you paint the walls on the inside of the property, or change the carpet, you can increase its value relatively quickly and then sell for a profit.

This strategy can often be used by investors who are just starting out and need more equity to become ‘Buy and Hold’ investors.

2. You Get The Money Straight Away

If you buy a property, renovate it, and then sell it, you get access to the profits straight away (after tax).

It’s an immediate pay-off, whereas under the ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy, your pay-off is down the road through long-term capital gains and cashflow.

3. Personal Satisfaction / Thinking It Looks Good On TV

The other reason people think about going down the ‘Buy and Flip’ path is emotional.

Although we may not all admit it, there is an innate romanticism about executing a ‘Buy and Flip’.

As mentioned above, us Kiwis like the idea of painting a room, ending our day tired and covered in paint droplets. It’s a bit of a dream – being hard at work while imagining our future gains.

One prospective investor once said to us here at Opes Partners: “I’m more excited about transforming a dunger and winning Resene Renovation of the Year, than making money … although money is quite exciting”.

Just to be really clear, some ‘Buy and Hold’ investors will also renovate. The key difference between the ‘hold’ and the ‘flip’ is whether you keep the property after it has been renovated.

Hold = keep the property. Flip = sell the property.

1. ‘Buy and flips’ is “one and done”

The biggest drawback of a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy is that once you sell the property, you don’t make any more from it.

While that sounds obvious, it means you don’t get any of the benefits from holding the property over the long term. There is no enjoyment from long-term capital gains from the house increasing in value, or receiving cashflow through rent from future tenants.

2. Projects go over budget

Sadly many, if not most, construction projects go over budget and cost more than originally anticipated.

But, if you are executing a ‘Buy and Flip’, going over budget has the potential to make the entire investment unprofitable and in some instances not worth the time you’ve invested.

Let’s say you invest in a property that needs electrical work. It can be hard to know exactly what needs to be done to fix an electrical error before you purchase the property.

Once tradesmen start work they might find there are other, unanticipated issues, that require more work, time and cost to complete.

3. Easy to mess up / higher risk

If you are not a professional tradesman it can be easy to mess up building works, repairs, maintenance, landscaping and painting yourself.

Not only is there a risk the work you undertake might not be completed correctly, but there’s also a risk you might ‘over-capitalise’. This is when you undertake work and spend time and money in areas that don’t increase the value of the property.

4. Takes time and can be stressful

Most renovation projects require the investor to make many of the improvements themselves. This is because without the investor’s own labour, some renovation projects wouldn’t be profitable.

This means that ‘Buy and Flip’ investors need to spend a lot of their own time, outside work, to make the project happen.

This often requires a lot of stress and late nights for the investor and their families.

Although that might seem fun when it’s other people doing it on TV, it’s a lot harder to do in real life.

5. You will usually need to buy a property in your city

Because ‘Buy and Flip’ investors usually complete most of the repairs and maintenance themselves, it’s therefore impractical for an investor to buy outside the city they live in (most of the time).

The result of this could be missing out on better opportunities outside of their home city.

For instance, investors located in remote areas or small towns in Otago can always undertake a ‘Buy and Hold’ strategy, because there is nothing stopping the investor buying in Christchurch or Auckland.

However, if they want to flip a property, they may find this difficult if there isn’t the right stock in their town. In addition, it is likely to be impractical to travel and complete a renovation themselves in another city.

It’s not impossible, but it is less practical.

1. Find a property you can add value to with your skills

The first step in a ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy is locating a property requiring the repairs and maintenance you:

2. Gain knowledge about doing renovations and the construction sector

Some understanding of the construction sector, so you can undertake the repairs and maintenance required, is a big plus. If you don’t have this knowledge already, you can start learning. Here are a few resources we recommend:

The ‘Buy and Flip’ strategy is a good option for people with a background in construction who have the skills and expertise to conduct renovations.

It is also good for investors who want to be active and hands-on with their investments, and who have the time available to do so.

There are some exceptions to this, which we will go through below, but those strategies tend not to be used as often.

Most property investors will begin their portfolio either using a cash deposit or an existing home to get started.

The reason you either need a cash deposit or equity from your own home is because most New Zealanders who invest in property can’t purchase a property outright.

What we mean by this is if you want to purchase an investment property worth $600,000, you probably don’t have $600,000 lying around spare in your bank account.

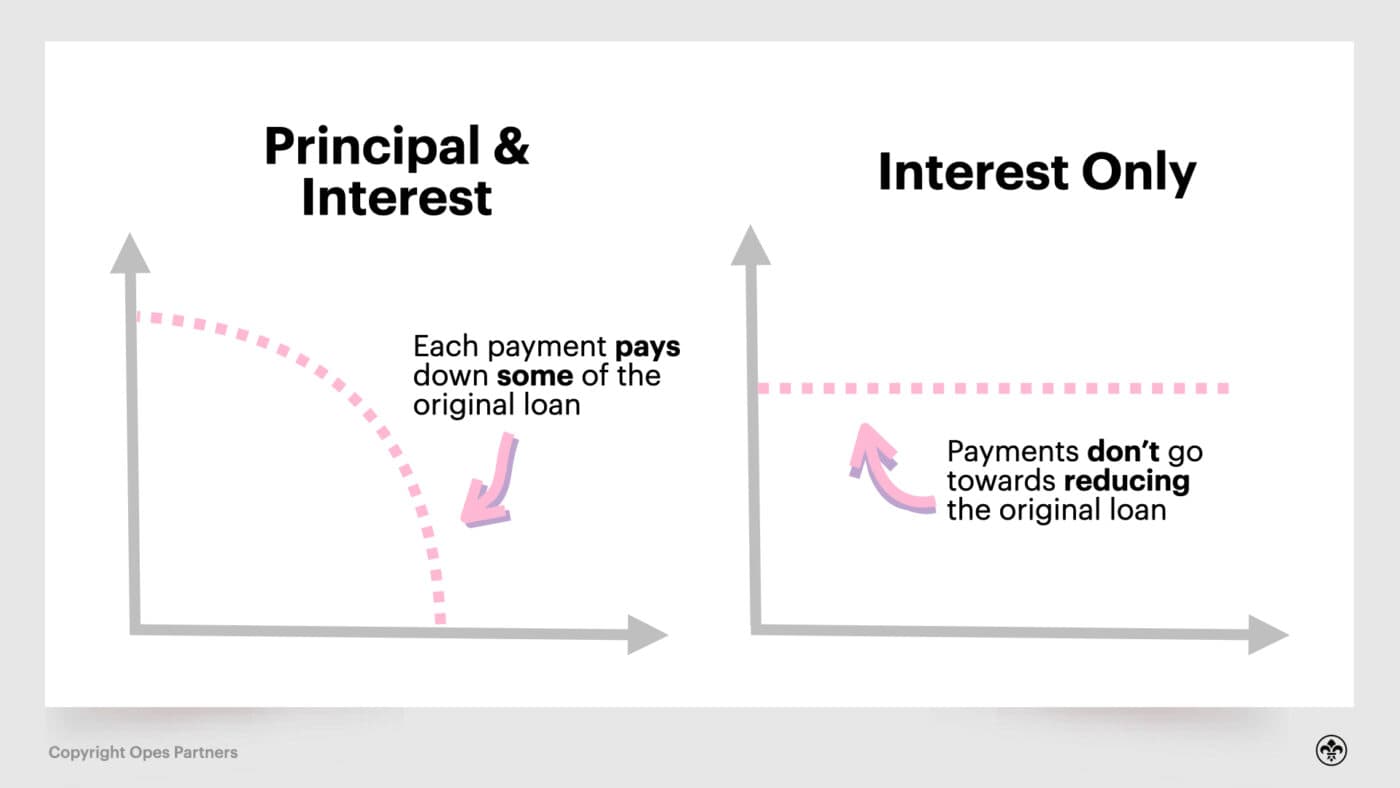

Instead, you need to get a mortgage from a bank to purchase the property.

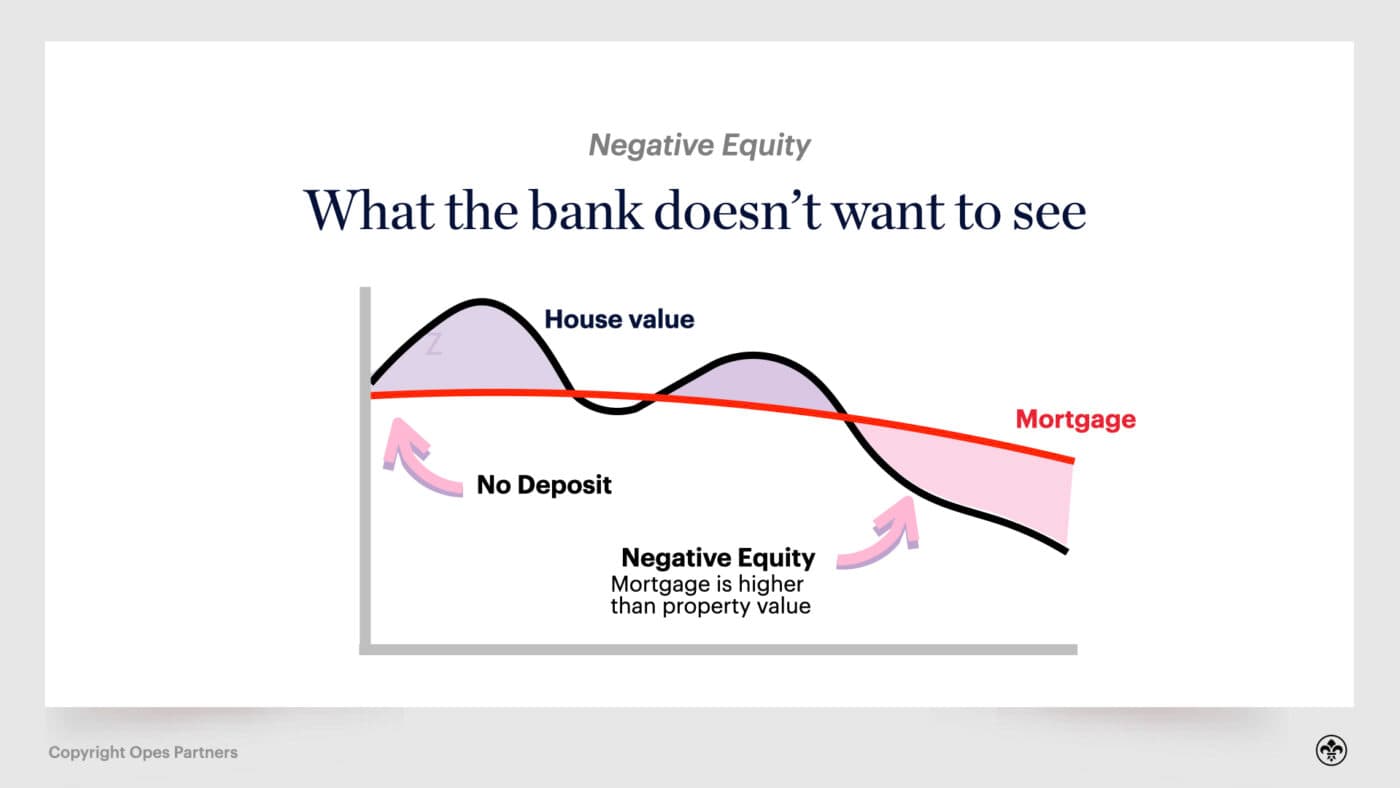

However, banks won’t typically lend an investor 100% of the money to buy the house. So, you need a deposit.

This is really basic, but it’s important to understand the reason why investing in property is the way it is.

There are two reasons a bank won’t lend you a 100% loan secured against a single property.

When a bank lends you money, you’ll need to pay interest on this amount each year. This is what the banks charge for lending you the money to buy the house in the first place.

You decide whether you pay this monthly, weekly or fortnightly.

If you don’t make your mortgage payments, the bank will repossess the property. In other words, they’ll take it off you and sell it to get their money back.

You then receive any leftover money after they have been paid back (minus any costs to sell the property, like real estate agent fees).

But, because the bank doesn’t want to lose money, they require you to have a buffer within the property. So, if the house sells for less than what you paid for it (or it’s sold at a discount because they need to sell it quickly), the bank is paid back in full.

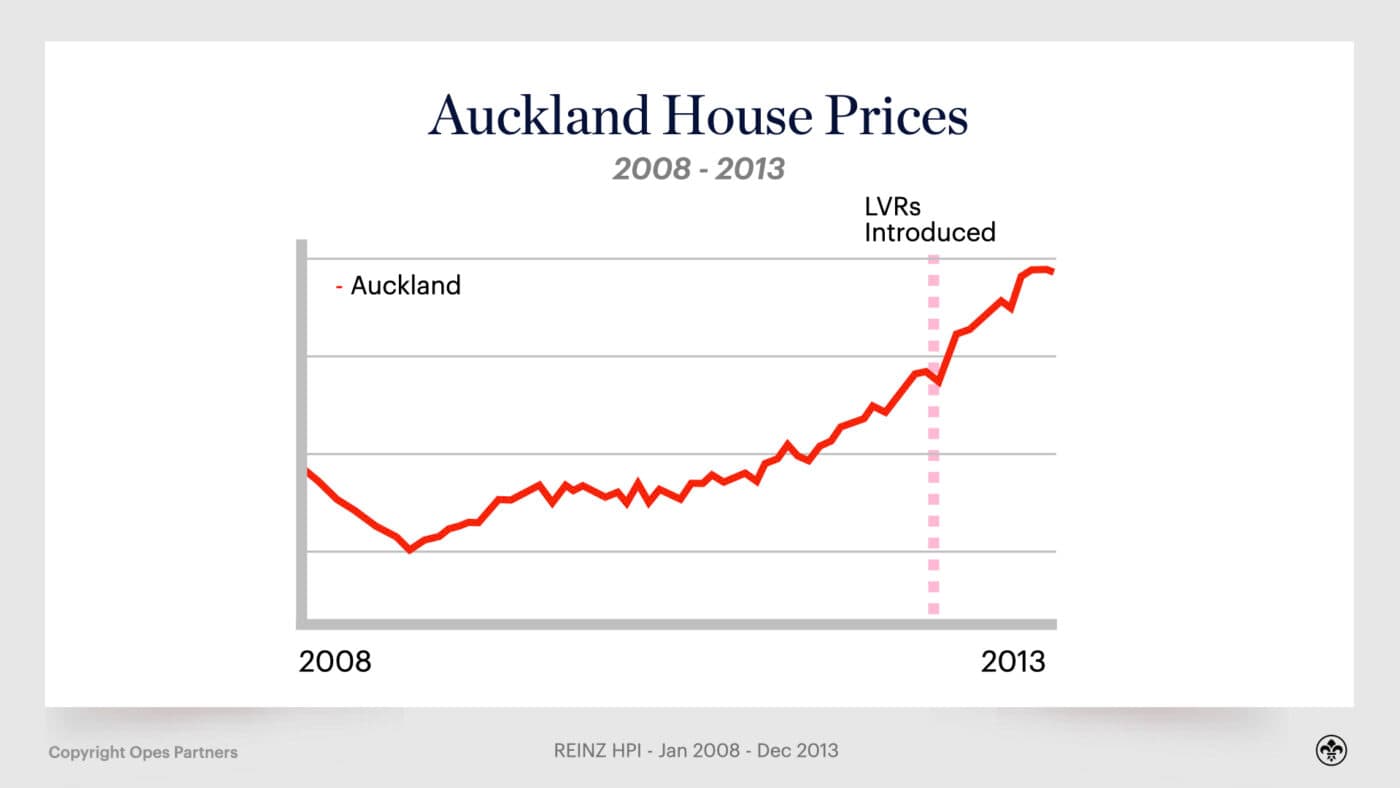

The other reason you need to pay a deposit is the government requires you to, through the Reserve Bank. This is due to the Loan to Value Ratio restrictions (LVRS).

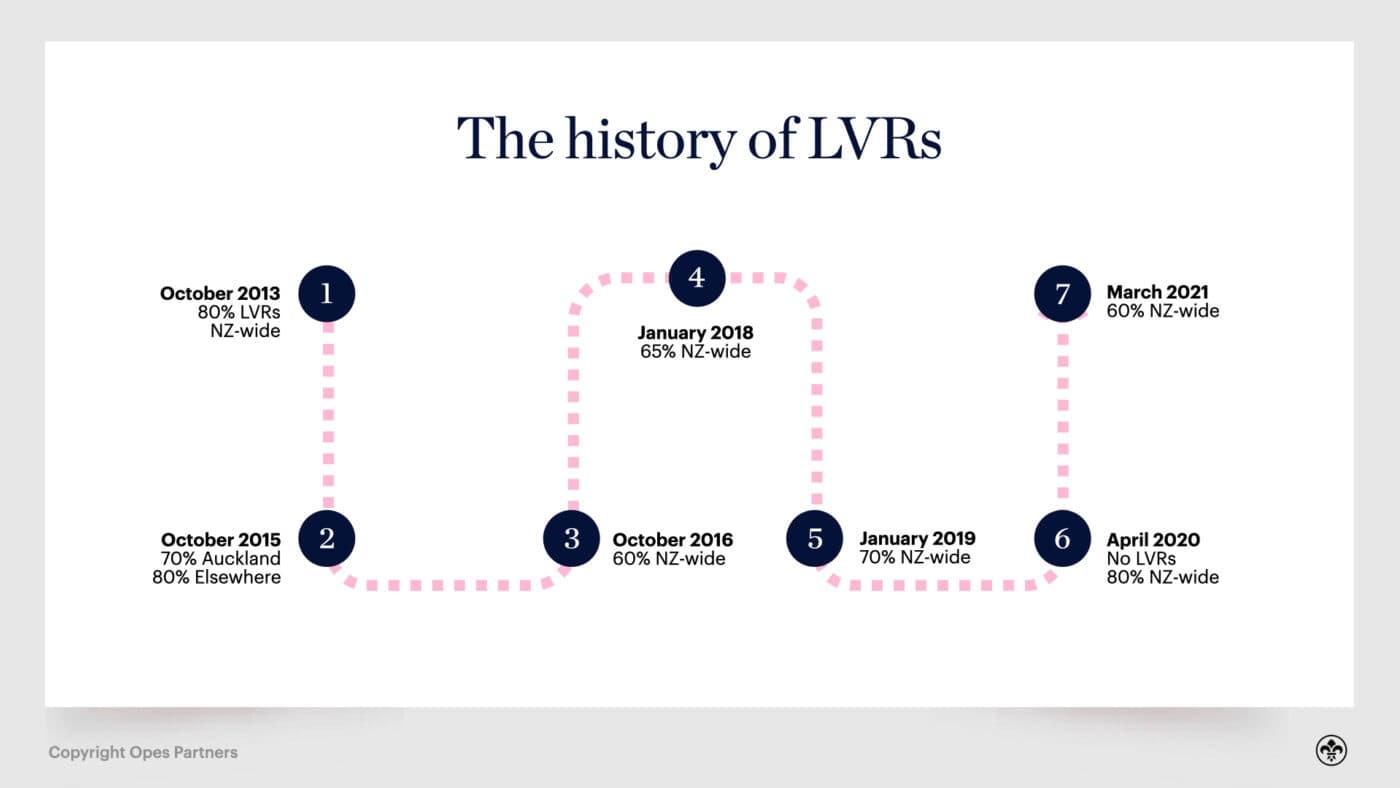

These new rules were first introduced in October 2013 to calm rising house prices in Auckland. Needless to say, they didn’t work.

Technically, these LVR restrictions limit the amount a bank can lend you compared to a property’s purchase price or value. The flipside is they set minimum requirements for how much deposit home buyers and property investors need in order to make a purchase.

The reason behind the Reserve Bank’s decision was to make it harder for investors to buy multiple properties quickly. There was a belief investors were causing the Auckland housing market to overheat, and the Reserve Bank wanted to slow down how quickly house prices were increasing (more on this below).

The amount of deposit an investor needs to buy an existing property under the Loan to Value Ratio is currently 30%.

However, it is important to know there are ways to work around the Reserve Bank’s rules and purchase property with a lower deposit.

For instance, new-build properties bought directly from a developer are exempt from LVR restrictions. The rules don’t apply.

So, in practice, you can purchase a new-build investment property with just a 20% deposit.

But we’ll talk more about the strategies you can use to purchase with a lower deposit shortly.

However, before we do, you need to know these restrictions will change over time.

Since this guide was originally written in 2019 the LVR restrictions have moved from 30%, to 0%, back to 30%, then again to 40%, to 35% and now back to 30% where they sit today.

And they have moved at least 8 times since they were first introduced.

What’s the key message here? The Loan to Value Ratio restrictions can, and will, change over time. So keep an eye out. If they loosen, perhaps you’ll be able to make a purchase. If they tighten, you may no longer be in a position to invest in property.

The LVRs in New Zealand are currently:

Put simply this means if you’re buying a property to live in yourself, the bank can lend you up to 80% of the property’s value as a loan. So, you’ll need a 20% deposit.

However, if you’re buying an existing home as an investment property, the bank will only lend you up to 70% of the property’s value as a loan. So, you’ll need a 30% deposit.

Yes, property investors require a higher deposit than owner-occupiers.

Let’s jump into an example. Say you want to purchase a $600,000 property.

If it is a personal home for you to live in, you need a $120,000 deposit (20% of $600,000).

But, if you want to buy the property as an investment, you need a $180,000 deposit (30% of $600,000).

This is why some first home buyers will purchase a property to live in for a short time, converting it into an investment property later - especially if they can’t afford to buy in their ideal location. More on these strategies in a moment.

There is a catch with all of these LVR rules. They don’t apply in every situation and there are exemptions.

For instance, brand new properties, such as new-builds, don’t come under the rules.

This means if you purchase a brand new property for investment purposes you only require a 20% deposit. The bank will lend you the other 80% of the property’s value.

Why would the government make this exemption?

Because New Zealand has such a large housing shortage, the government wants to encourage developers to build new properties.

Incentivising investors has two main perceived benefits:

The size of the deposit you'll need to invest, therefore, depends on whether you plan to invest in a new property or an existing property.

To give you another example, let’s say you have a $100,000 deposit and you want to buy an investment property.

If you choose to invest in an existing property the maximum price you can pay is $333,000. That’s broken down into your $100,000 deposit (30%) and the $233,000 the bank will lend you (70%).

That $333,000 isn’t going to buy you much at all.

But if you were to purchase a new-build as an investment property, then the maximum price you can pay is $500,000. That’s $100,000 of your deposit (20%) and the $400,000 the bank will lend you (80%).

If you want to figure this out quickly, you can use the equity and leverage calculator on our website. Or, play around with the one below.

But if you’re out at open homes looking at properties, here’s how to do the math in your head or on your phone.

Either take the deposit you have available and divide it by 0.2 (if you plan to invest in new properties) or you can divide it by 0.3 (if you plan to invest in existing properties).

Alternatively, if you already have a property in mind, you can take the purchase price of a property you’re considering and multiply the purchase price by 0.3 (if it is an existing property), or multiply it by 0.2 (brand new property).

Now, at this point you might be thinking:

“What if I don’t have a cash deposit?” or, “didn’t you say I could start investing if I have my own home already?”

Absolutely, so in the next section we’ll talk about how to find/create your deposit.

Right at the start of this article we said there are two ways to get your investment deposit.

You could either use cash, which is the obvious way. Or, the way most people fund the deposit for their investment properties, through the equity within their own home.

Let me explain.

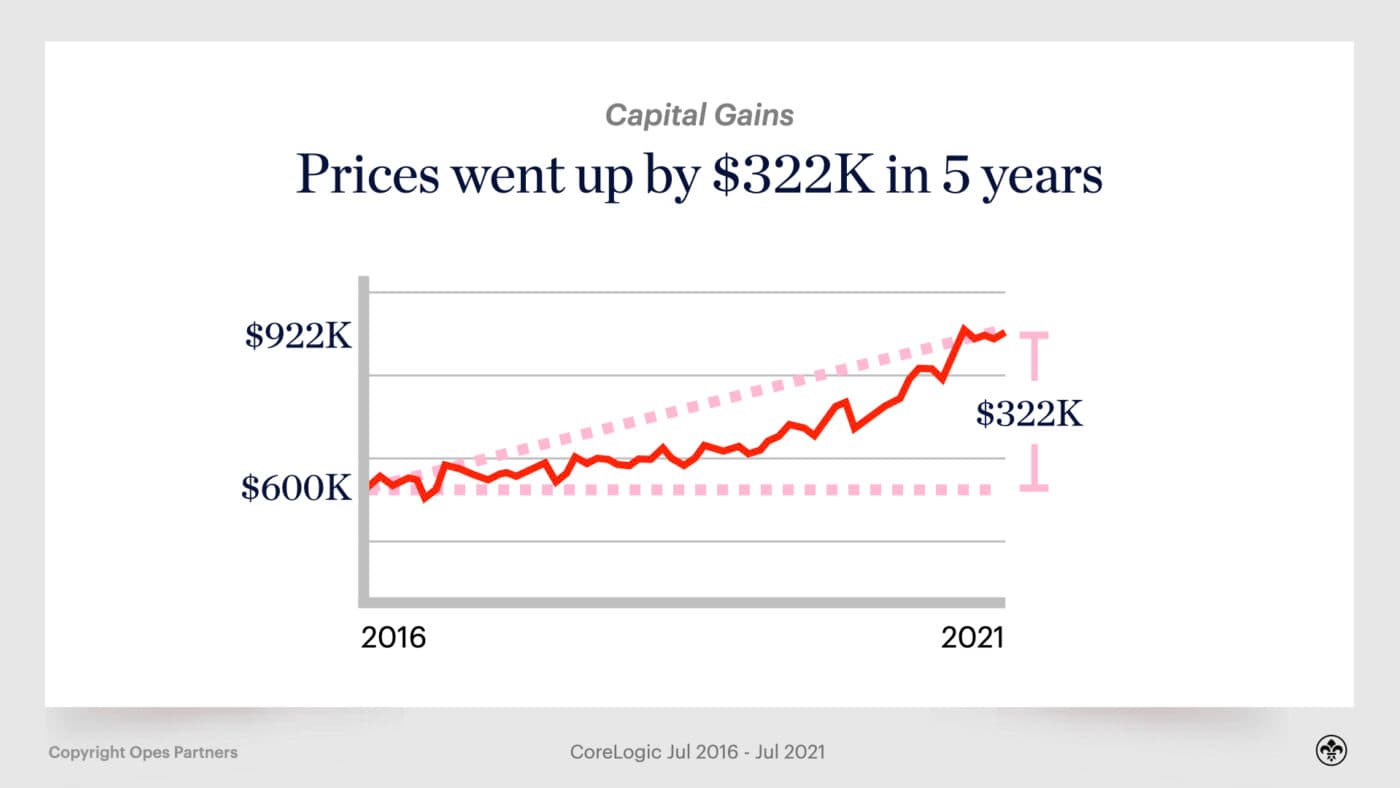

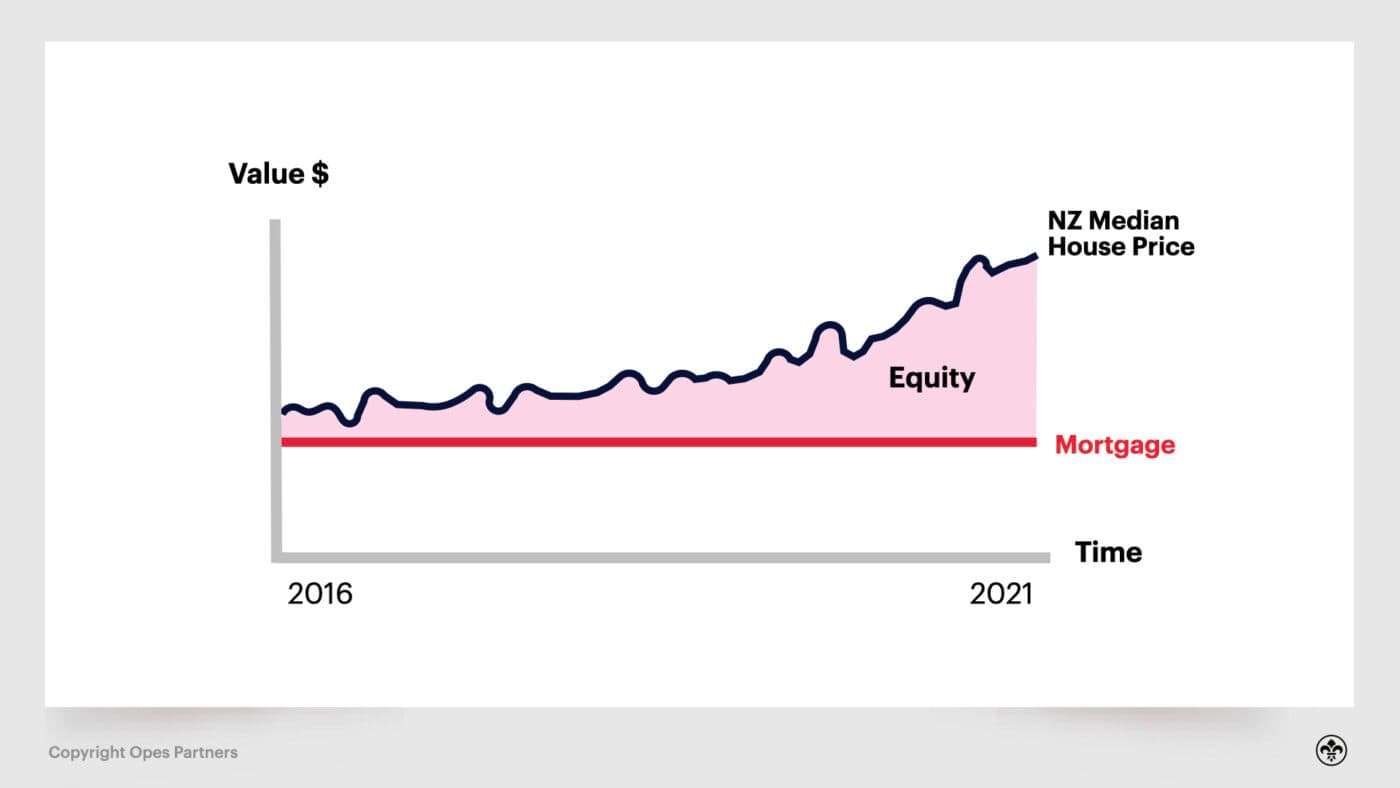

From July 2016 to July 2021 the average New Zealand property increased in value from $600,000 to $922,000 – an astonishing $322,000 increase, according to Property Value and CoreLogic data.

So, let’s say you bought a house in 2016 for your own use. If the house was priced at $600,000, under the LVR restrictions for owner-occupiers at the time, you would likely have taken out a mortgage of $480,000 (80% of $600,000).

This means when you bought the property, you used a $120,000 deposit. This means you now have $120,000 worth of wealth or equity within the property.

You calculate this equity by taking the value of the property, and subtracting the loans that are secured against the property.

One of the greatest benefits of property is although you only have $120,000 worth of equity initially, as the house goes up in value you get to keep 100% of the increase in value (what’s known as ‘capital gain’).

Now, let’s return to 2022 and talk about the two things that would have happened between 2016 and 2022.

1. You would have paid down some of your mortgage

Over the last 5 years you would have paid off a small part of your mortgage.

Let’s say your $480,000 mortgage was set up on a 30-year loan term at an interest rate of 4% and you were making the minimum payment each month.

After 5 years (2022), your mortgage would have gone down to $434,000. So you would have paid off just under $46,000 worth of debt. Yes, I know it doesn’t seem like a lot after 5 years, but that’s the facts.

But something else also happened.

2. Your property increased in value

As we have said, because of value increases that average house price tag is now $922,000 (as at July 2022). So, if you had bought the average house, you would have received $322,000 worth of capital gain.

So, let’s re-run the numbers to see what equity you now have.

You have a house worth $922,000 and a mortgage of $434,000. This means that your $120,000 deposit has grown to $488,000 worth of equity (an asset) within your home.

The reason all this matters is that you can use some of this equity as your deposit when you go to purchase an investment property.

Here’s a video walkthrough of how to do it from Opes Partners Managing Director Andrew Nicol. But, if you prefer to read, we’ll also write it all out below ...

Remember how we said under the LVR restrictions you can borrow up to 80% of the value of your own home?

Now that your house has gone up in value from $600,000 to $922,000, you can borrow more money against it.

This means going back to your bank, or your mortgage broker, and increasing the size of your mortgage – potentially up to 80% of your property’s new value.

You can then use the extra money as the deposit for an investment property.

Borrowing against this equity effectively unlocks cash within your home (‘dead money’ as we like to call it) and means you can begin to invest and get a return from it.

Because your house is now worth $922,000, multiplying this by 80% means you can get a mortgage of up to $737,600.

However, because you already have a mortgage of $434,000, you can’t take out another $737,600. You can only take out the difference.

In this case you’d be able to get an additional loan of up to $303,600 ($737,600 - $434,000).

This is why property investment is so accessible to many New Zealand homeowners, because you may already have a deposit sitting there ready to invest.

OK, we’re on the home stretch now.

Here’s the situation: You’ve got $303,600 to use as a deposit. What can you do with it?

Well, it depends on whether you buy a new-build or an existing house.

If you buy an existing property, then you could purchase up to $1,012,000.

$1,012,000 = $708,400 (70% loan) + $303,600 (35% deposit).

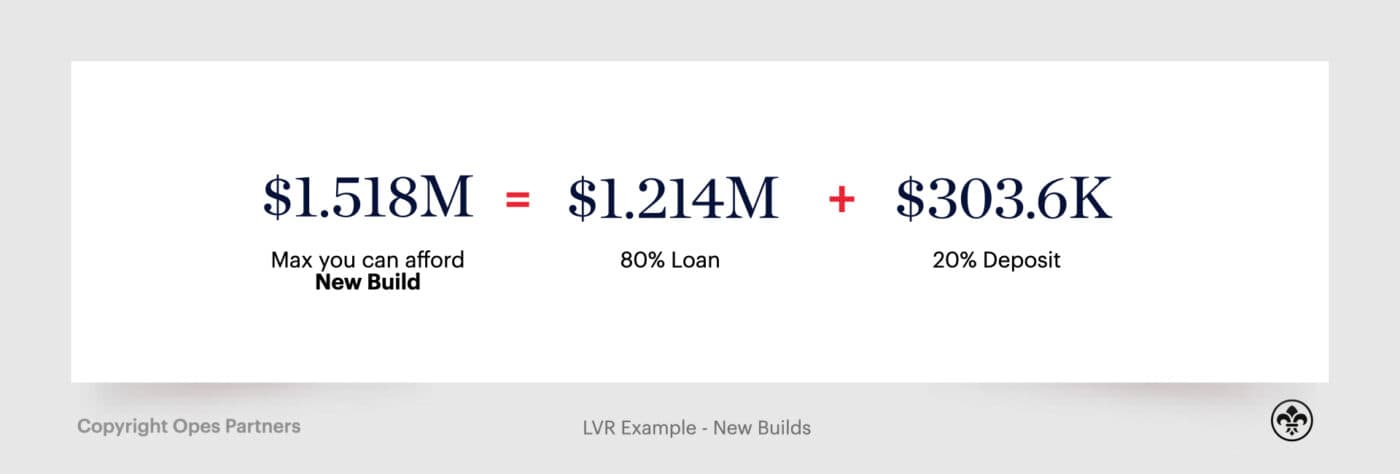

However, if you were to buy a new-build property then you could purchase an investment property worth $1,518,000.

$1.518m = $1,214,400 (80% loan) + $303,600 (20% deposit).

Now in practice you’re probably not going to go and buy $1.5m worth of new-build properties, but you might buy 2 new-build properties spread around the country.

For instance, you might buy a $850,000 new-build townhouse in Auckland and a $650,000 townhouse in Christchurch.

So, it’s not like you need to spend it all on one property.

The bank will (almost) always require you to have a deposit for an investment property.

So, if you don’t have cash or your own home, then you’ll need to get creative with how you pull your deposit together.

There are a few things you can potentially do to pull together a deposit if you aren’t able to meet the 20% threshold for a new-build investment property, by either savings or equity.

If you don’t have cash or own your home, then you may be a younger person (say under 35).

This does not stop you from becoming a property investor.

The most common way young people pull a deposit together for investing in t heir first property is to tap into the “Bank of Mum and Dad”.

The “Bank of Mum and Dad” is a commonly used saying that is often misunderstood.

It’s not about using your parents' income to buy you the things you want. Rather, it’s about using the equity within their home to help you buy your own home or a rental property.

This works the same way as the example above, where the existing mortgage is ‘topped up’ to create a cash deposit.

Just like the average house in New Zealand has gone up in value over the last 5 years, your parents’ home has also gone up in value since they’ve owned it.

This means they have likely gained equity for you to potentially use.

If this applies to you, your parents could borrow against their home to help you make a purchase.

Most parents and children then work out an agreement about how that money would be paid back. Typically, the younger person would make the repayments on the mortgage the parents have lent them.

We’ve already discussed Loan to Value Ratios, but one important thing we didn’t mention is these restrictions don’t apply to all bank lending.

The rules actually state some of the banks’ lending can be to high LVR borrowers.

This means if you have a deposit, but it’s not at the 20% or 30% required, you can still get a loan, but you’ll be classed as a high LVR borrower.

Right now, up to 25% of bank lending to owner-occupiers can be ‘high LVR’ (less than 20% deposit).

For instance, we frequently see first home buyers purchase a home to live in with just a 10% deposit. This could be converted to an investment property at a later date if the purchaser wants to.

Instead, you might like to consider a non-bank lender. These financial institutions will lend you money to invest, but they are not considered a bank and so don’t come under the LVR restrictions.

It’s not unheard of for an investor to purchase an existing rental property with a 20% deposit when using a non-bank lender.

However, just be aware that these sorts of lenders will charge higher interest rates, which you’ll need to factor into your calculations.

The best way to work through these sorts of situations and secure these types of loans is through a mortgage broker.

Mortgage brokers keep up to date with the bank’s policies and know which lender is offering money to different investors right now.

If you are in this situation you should definitely talk to a good broker. Remember, most mortgage brokers are paid by the banks, so their services are free. More on this below.

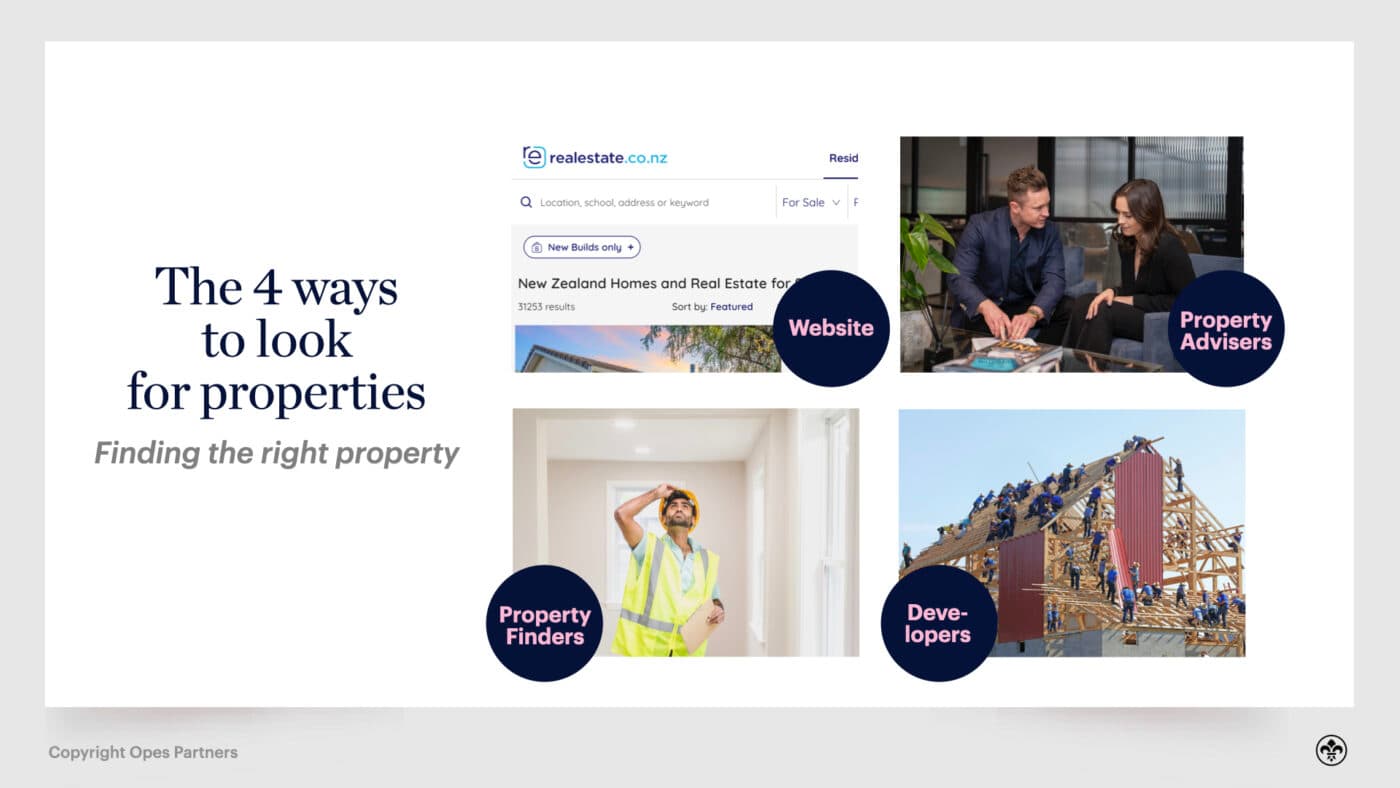

So, you have chosen a property investing strategy and have an idea of how much you can afford to invest. Now, it’s time to decide where to look for an investment property.

This chapter will focus on the Buy-and-Hold investment strategy for finding and analysing properties, as this is the more common strategy. If you’re a Buy-and-Flip investor, the way you look for properties will be different.

Property investors are, effectively, going into business for themselves - a business that provides rental accommodation.

Now, the reason residential property is an attractive asset is because you can earn money in two different ways because you are operating in two separate markets.

Simultaneously you can achieve:

Because your property investing business will operate in these two separate markets, you need to ensure the property you choose (your product) can work in both.

For this your property needs to achieve:

Both of these are market-led. This means you need to start, not by looking at a specific property, but finding the market you want to operate in.

Since each region’s property market operates somewhat independently, you need to choose a city.

If you choose to live and work in one city, you usually can’t live in a property in another city.

For instance, if you want to live in Auckland because you've got a job, or want to be close to your kids, you're going to buy or rent in Auckland – maybe Hamilton at a stretch. But there’s no way to practically live in Christchurch.

In economic terms, properties in different cities are not good substitutes for one another. A house in Gisborne is not a good substitute for a house in Auckland, especially if you’re someone who wants to live in Auckland.

So, the property market is very closely tied to the long-term prospects of a city. Do people want to live there? Do people want to move there? Is the population increasing or decreasing? Are enough houses being built to keep up with demand, or is there a supply shortage forming?

This is why before choosing a property to invest in, you must decide which region or city you want to target.

When it comes to capital growth, it’s often more important to pick the right city, rather than the right property.

Let’s take another example to illustrate this.

Say you find a great property. It’s well-built, has 3 bedrooms, 1 bathroom and a large section, and it only costs $221,250.

The question now is: Should you invest? The answer: It depends … where is it?

If that property is in a tiny town like Patea (in South Taranaki) where the average house is worth only $221,250 – then the answer is likely to be “no”.

This is because you’re not likely to achieve stable increases in the value of your property over the long term.

Patea as a town has:

This isn’t to disparage or put down Patea as a place to live. It’s a great little town and Ed – one of this guide’s authors – grew up playing squash at the local club. However, it doesn’t have the fundamental factors most property investors are looking for.

Will property prices ever increase in a small town like this? Yes, there is likely to still be some growth but it will be driven by external factors. For example, low-interest rates and the bump the whole of New Zealand saw after the Covid-19 pandemic.

But, which would give you the greater confidence to invest:

The bottom line is you must find the right town or city to invest in first, before you start looking for the right property within that city.

So, how do you do that?

Below we outline the 6 factors to look for when choosing a city or town to buy an investment property in.

Note: All the data shared below is available free elsewhere on this website. So be sure to check out our property market pages to dig further into the data.

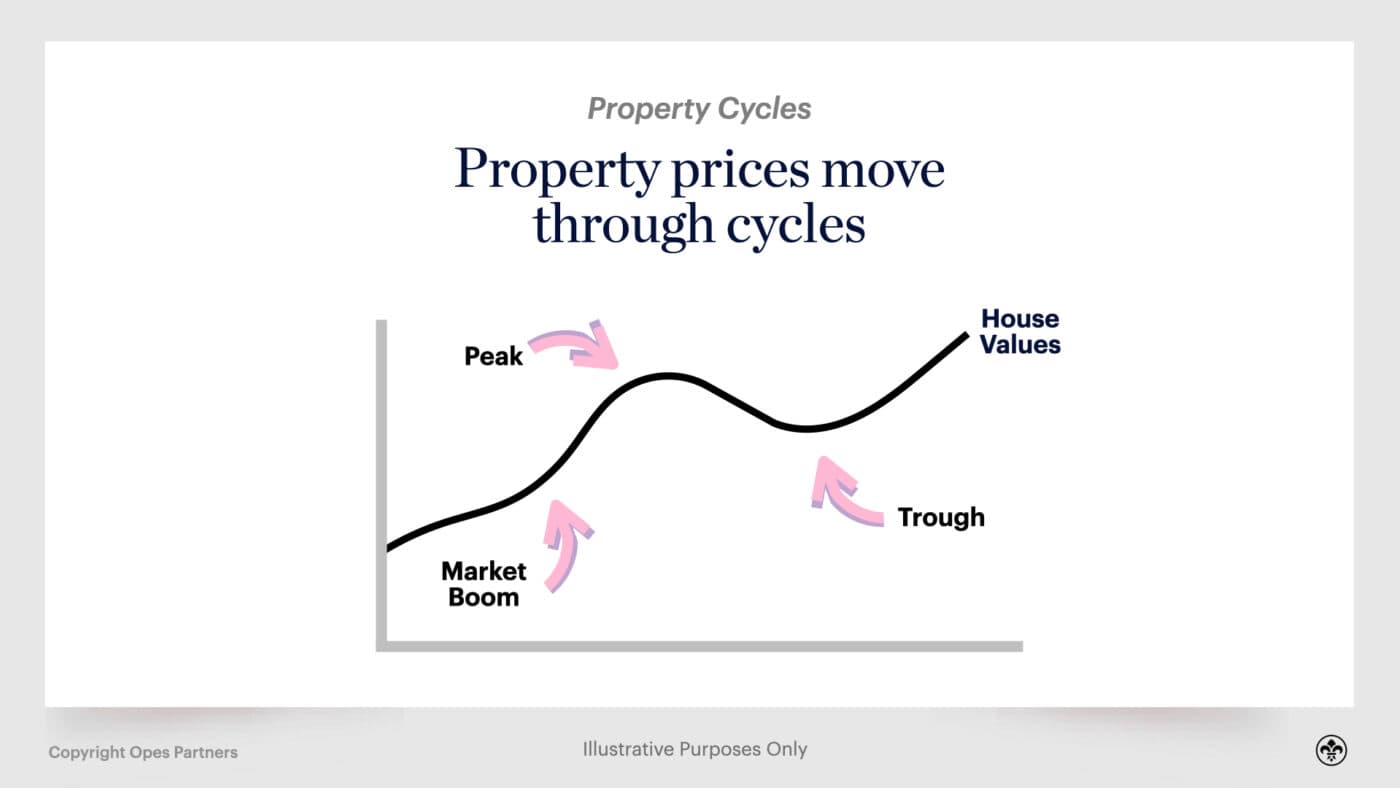

It’s often said all assets (including property) move through economic cycles. Sometimes prices are booming and there is confidence in property. Other times that confidence wanes and prices start to droop.

But, as we said above, because properties in each city aren’t good substitutes for one another, each region operates within its own property cycle. To say this in another way, property prices in Auckland might be going berserk, while those in Wellington are relatively flat. This happened between 2012 and 2016.

However, between 2016 and 2020, Wellington property prices increased quickly while Auckland remained stagnant.

So, it’s imperative we as property investors locate regions that are in an attractive part of their property cycle.

The way we do this is by asking:

Let’s go through an example to talk through the theory of those two points.

Over the last 30 years (1992 - 2022), Southland’s median house price has been 47% of the New Zealand median price.

So on average if the New Zealand median house price was $500,000, Southland’s would be $235,000.

But markets go through different cycles and sometimes a region’s property prices will be above that average. For instance, right now Southland’s median house price is 50.8% of New Zealand’s median price.

So house prices are 7.19% above their long-term average in this model.

Does this mean Southland’s property prices will crash? No.

Does this mean house prices in the region might not increase in the future? No.

But, it means there may be better opportunities in other parts of the country to find a good investment property if we are looking for healthy medium-term capital growth.

So you may wonder, where are the most undervalued and overvalued regions in New Zealand right now?

Here’s a list of NZ’s 15 most populous regions with where they sit under this model:

If you’re looking for the most up-to-date data, you can find it in the property markets’ section of this website. Here’s a list of the regions we cover:

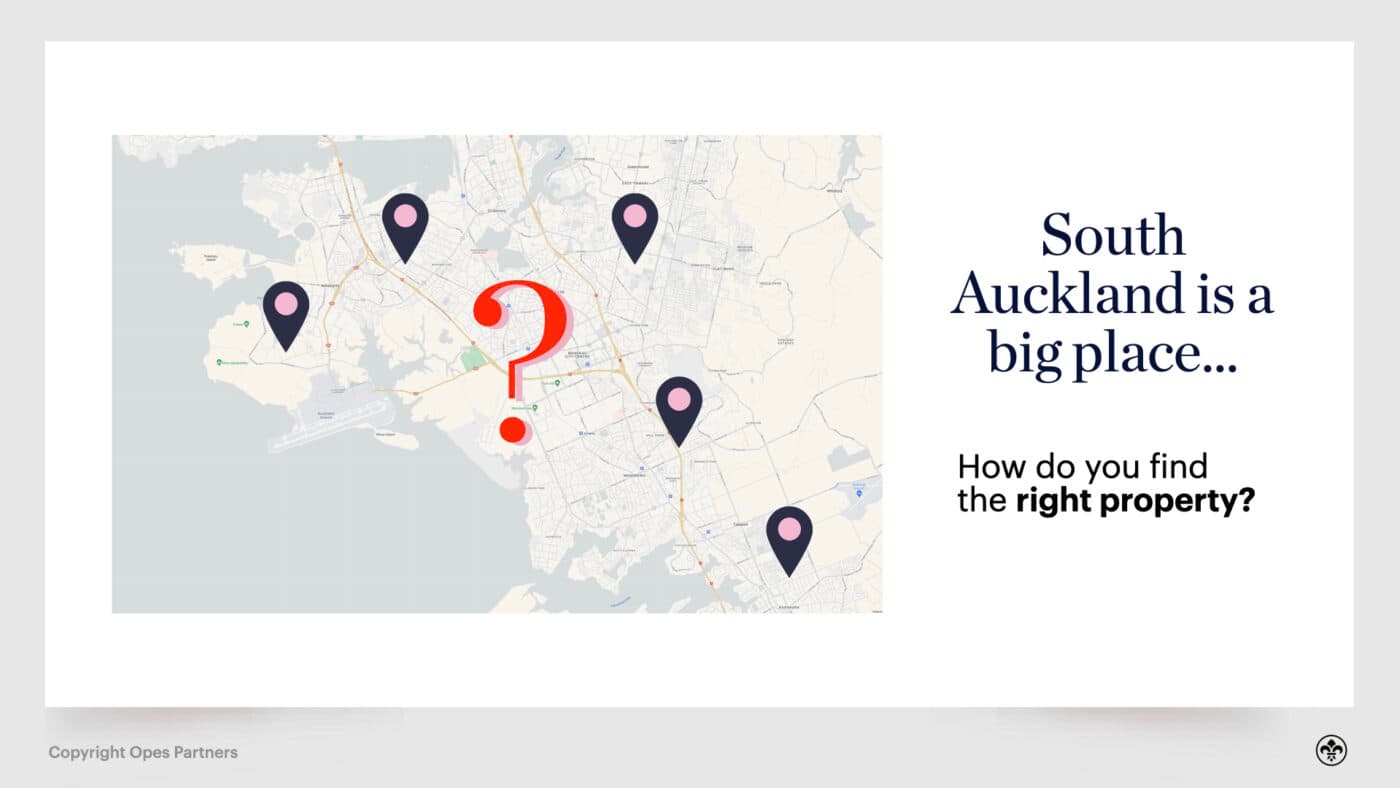

It’s all very well finding an undervalued region, but some parts of that region may be more undervalued than others.

Let’s not forget, some of New Zealand’s regions are massive. The Waikato region, for instance, goes all the way from the top of the Coromandel Peninsula down to the bottom of Turangi in the Taupo District. That’s over a 4-hour drive.

So, we need to break the larger regions down into council areas to better target our search for investment properties.

For instance, here is the Canterbury region broken down into each council area. The map then shows where each council area is within its property cycle.

You can see the most undervalued region as at July 2022 was Waimakariri, which is 26.55% below its long-term average.

Whereas the MacKenzie District is 25.28% above its long-term average.

Both districts are in Canterbury, which is seen as undervalued by this model. However, right now, one district appears to be more attractive for property investment compared with the other.

The next step is to look closely at population projections.

When you eventually come to sell your investment property, you want to ensure it will have increased in price.

One indicator of this is population growth. More people = more demand for housing = higher house prices. You can see that trend in the data when we graph annual population growth with annual house price growth.

So, it is important to look at the projected population for the city you are analysing.

Take the Auckland property market over the 19 years between 2000 - 2019.

Between those years, the city’s population grew by 389,000 people – that's 25%, or the size of Christchurch. Over those 19 years property prices increased from $240,000 to $860,000 – which is 250%.

It took 19 years for Auckland to add the size of Christchurch to its population. But the same level of population growth (around 390,000) is expected to be added to the city over the next 9 years.

What is that going to do to the demand for housing? How will that impact house prices? What will higher numbers of people in the city do to rents?

Well, it’s likely to have a positive impact on property investors who already own property in the city.

By now you are probably also picking up population growth is often distributed around a region. What do we mean by that?

Well, over the next 25 years (2018 - 2043), Canterbury’s population is expected to grow by about 19%. But that doesn’t mean the population in every part of Canterbury is going to increase by that amount.

Take a look at the breakdown of population growth by council area.

Here you can see some areas are expected to see enormous population growth. Selwyn District’s population is projected to grow 60%+ over this period, while Kaikoura’s population is projected to shrink 4.36% over that time.

What’s the lesson here?

As well as looking for a good region to invest in, you also want to dig deeper to consider what’s happening in each council area.

The other side of having more people in the city is ensuring they have the income to support higher house prices.

You might have a large population base, but if houses are unaffordable to buyers then there won’t be much room for growth in property prices.

There are two factors to consider:

There are a couple of ways economists try to track economic strength. GDP, which is growth per person (per capita), is something you’ll often read about in the papers.

But what you really care about isn’t how much businesses are doing in a region. What you do really care about is the income real families are earning. This where you might consider average (mean) household income growth.

Let’s talk about the Bay of Plenty region, since they haven’t got a mention so far in this guide.

Over the 21 years between 1998 and 2019 (the years we have current data for) the average household income in Tauranga increased 4.14% per year.

Over that same time-frame, household incomes in the Kawerau District (a small district also in the Bay of Plenty) grew by only 2.99%. That’s the slowest in all of New Zealand.

So, if you were considering an investment property in the Bay of Plenty region, putting all other factors aside, which would you rather invest in? Which area is going to be able to support higher rents? Which area will have the income to support higher house prices? Which area is likely to be more prosperous in the future?

If you’re like most property investors, you’ll probably gravitate towards Tauranga in this instance.

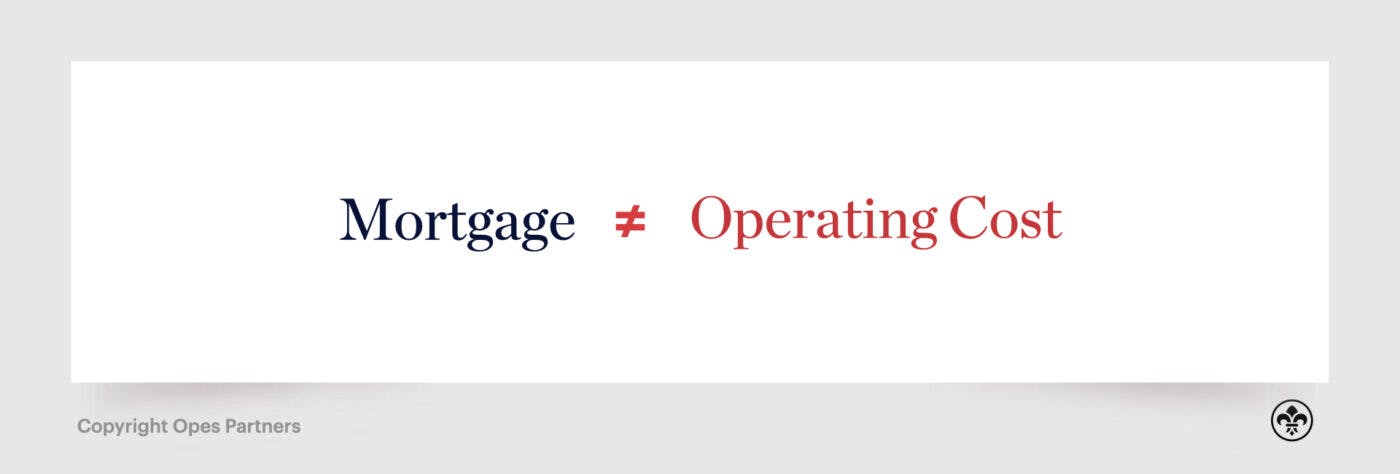

There’s a joke in property investment circles, which is: “You can’t use capital gains to pay your mortgage”.

It’s true, even if your property is increasing in value, you still need to be able to pay the mortgage. You’ll really feel the pain if you purchase a property where the rental yield is so poor you have to pay tens of thousands of dollars a year to top up the bank account.

So, a big part of becoming a successful residential property investor is ensuring you can hold the property over the long-term so you can achieve capital gains over time.

This is why when analysing a target city, you should compare rents with house prices to ensure they meet your investment appetite.

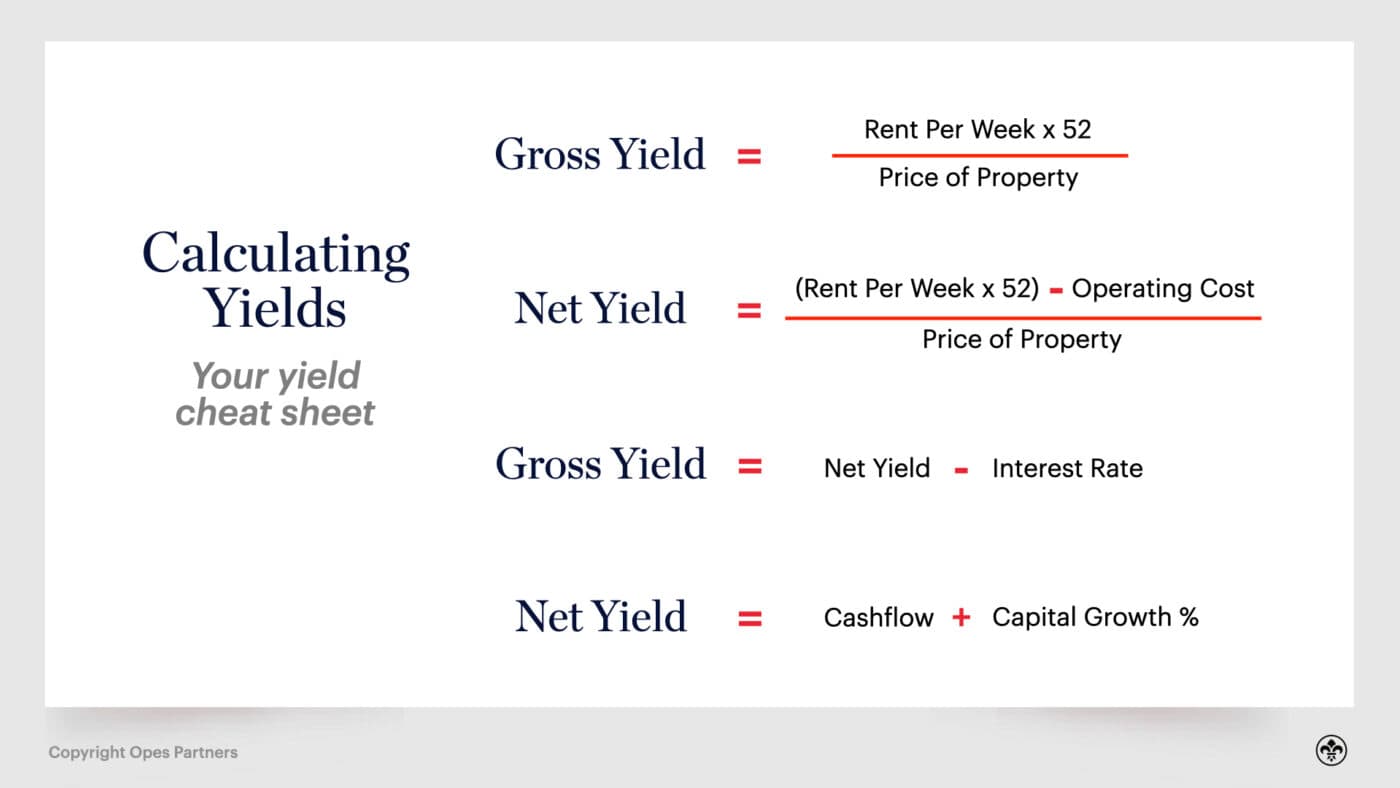

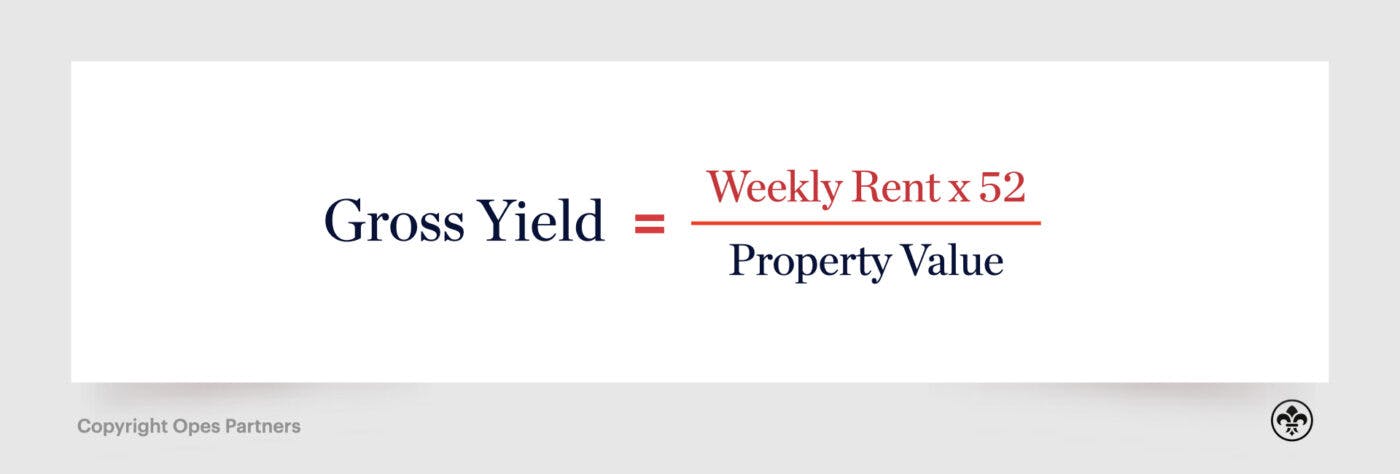

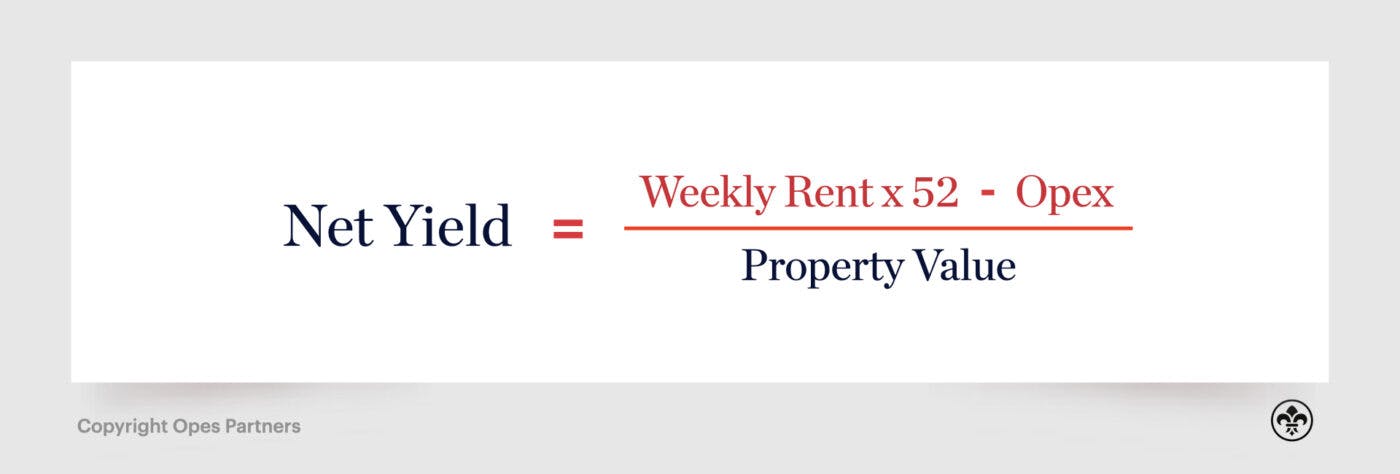

For instance, Auckland currently has an average rent every week of $611 for three bedroom homes, according to Barfoot and Thompson (August 2021). But the average sale price for that type of property was $1,060,000. That is a 3.0% gross yield (accounting for no vacancy).

Whereas Rolleston has an average rent every week of around $490 for 3 bedroom homes, and the average sale price for 3-bed homes is $675,000. This is a 3.77% gross yield.

This means it is much more affordable to Buy-and-Hold in Rolleston over the long-term. Not only is there a cheaper entry price, but there is relatively more income achieved each week to pay for expenses. Some expenses, like interest payments to the bank, are often proportional to the price of the property bought.

But this doesn’t mean you shouldn’t buy in Auckland. It just means if you do invest in Auckland, you need to be aware it will require more investment to get the capital gains.

Although gross yield isn’t always the most useful calculation when looking at a particular property (as we will discuss below), it is still useful when analysing a city or suburb to invest in.

So, finally, you’ve found a good city with good fundamentals. Now you need to make sure you can actually afford to purchase there.

The affordability of housing changes drastically around the country, and even within a region.

For example, take a look at the Waikato region to see how affordability can vary.

The average property in the Waikato region sold for $711,000 in July 2021, according to REINZ.

But the average property value in the Thames-Coromandel District is $1,085,000 (the most expensive council area in the Waikato), and the average property in the Waitomo District is only $300,389, according to propertyvalue.co.nz.

So, property investors will find some areas very affordable, but other areas more expensive. It’s important to keep this in mind as you’re searching for rental properties.

On your quest to look for high-quality investment properties, it’s important to note: Not every city or region is going to tick every box on this list.

After looking at the data, you’ll need to make a judgement call about where you believe is the best place for you to invest. That will be different for each individual.

For instance, if you have lots of money to invest, you might choose to purchase in Auckland. Property prices there are high and yields relatively low. But it’s got high population growth, good incomes and abundant industry.

If your affordability is low, on the other hand, you might only be able to purchase in a region where both prices, income and population growth are lower.

But, armed with these tools, you should be able to analyse a region and then make an informed decision.

If you would like extra credit, your next step might be to start digging into suburb level data, which means identifying specific areas where you want to look for investment properties.

That’s where you might look at a pair of maps, like the ones below, to identify suburbs that have had high capital growth in the past, and also relatively high yields.

For instance, here is a map of Auckland showing the suburbs that have achieved the highest capital growth between January 2000 and today.

And here is a map showing the current gross yields broken down by suburb.

This suburb level data is broken down for each of the four main cities in New Zealand– Auckland suburbs by price, Wellington suburbs by price, Christchurch suburbs by price, and Hamilton suburbs by price.

So, at this point you’ve chosen a property investing strategy, you know your budget and you’ve chosen a city to invest in.

Now, it’s time to go shopping.

Let’s imagine for a moment you’re walking into Briscoes.

As soon as you walk in through those glass sliding doors, what’s the first thing you look for?

Probably the signs hanging from the roof ... you know, the ones saying “homewares,” or “bathroom,” or “kitchen”.

These signs help move your feet in the right direction, closer to the pizza cutter you’re looking for on this particular occasion.

But, let’s say those signs don’t exist.

It’s going to take a lot of rummaging around, walking back and forth past the pillow section a million times for you to find the kitchen section, and eventually what you came in for – that pizza cutter.

Searching for an investment property can often be like walking into Briscoes for the first time, except there are no signs and every product doesn’t have a clear label. So, it’s hard to compare products easily.

For example, think about logging onto Trade Me or Realestate.co.nz. It’s not easy to figure out what makes a good investment property, which properties are going to be high growth, and which are going to be higher yield.

In this chapter we’re going to start putting up ‘department signs’ and breakdown the different ways you can categorise properties. Ultimately, this is going to result in you knowing exactly what to look for when you start hunting for properties.

There are three ways to categorise investment properties:

You’ll want to decide which type of properties to target since there are different laws, expected financial returns and constraints that apply, depending on which way you choose to go.

So, this chapter starts by walking you through each way to categorise properties. Then, in the final section, you’ll learn the different ways to find investment properties … because looking on Trade Me is not the only way.

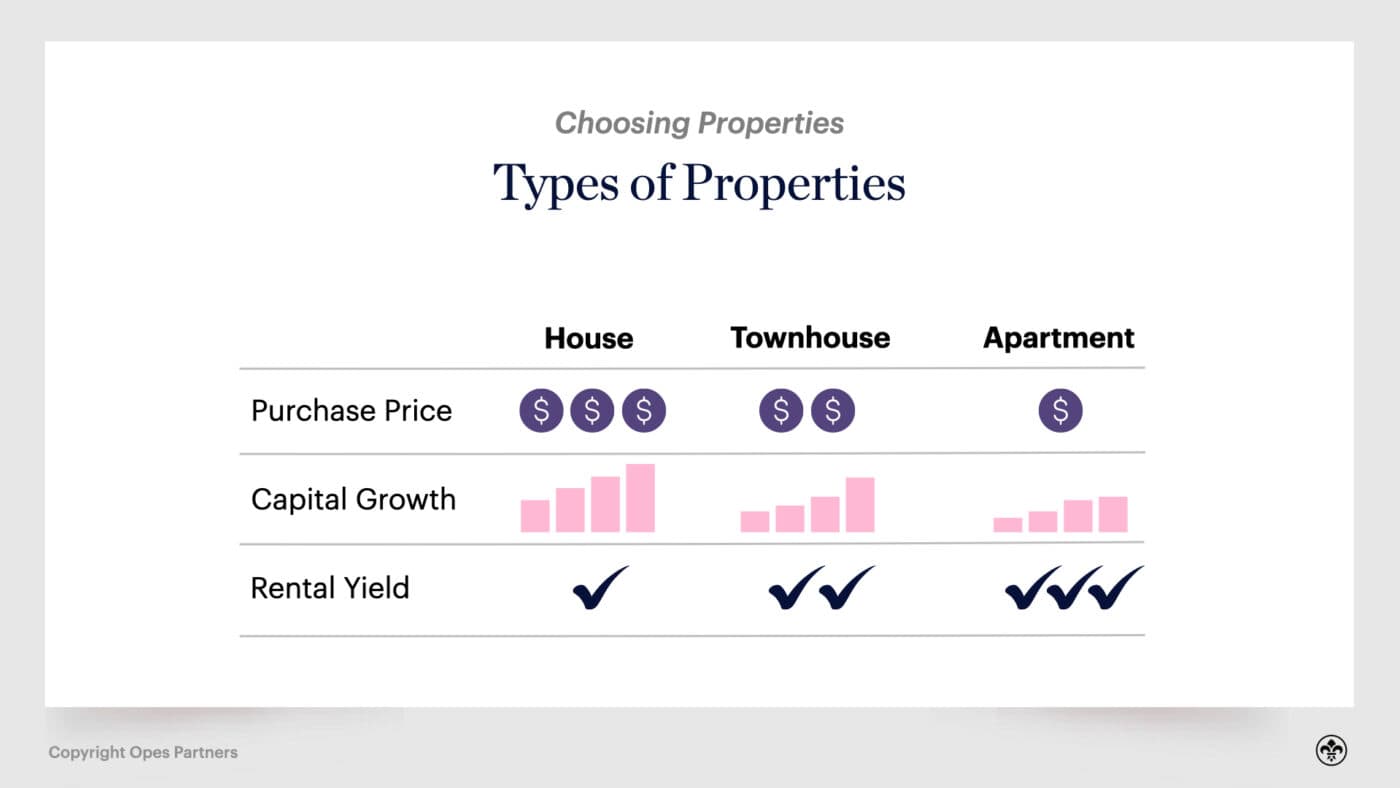

When we talk about property types we are specifically discussing whether the property is a: standalone house, townhouse, apartment, piece of land with nothing else on it, or something else.

A standalone house – sometimes known as a house and land package – is the quintessential Kiwi home. It is a house that is not connected or joined to any other houses, and is on its own plot of land.

More options to improve the property’s value

If you are an investor focused on renovations and adding value, then standalone houses are most often the best option for you.

This is because standalone houses have more land and often have a larger floor plan. As a renovations-focussed investor this gives you options.

If it’s an older property, you may be able to add additional bedrooms within the internal floor plan (i.e. without adding an extension to the property). You can also build a deck or outdoor living space easily, or improve the landscaping.

Both of these options will increase the value of your property and the property’s rental return.

If you have enough land you can add a minor dwelling out the back. Or, if you are more land-constrained, you can add a cabin (also known as a sleepout) so the property effectively has an extra bedroom, which increases your rent (but often not the property’s value).

With a standalone property, you can paint the exterior of your property if it is looking shabby. So, you have control over how your property looks.

Compare this situation with an apartment, where if you want to change or improve the exterior of your property you’ll need body corporate approval. This is a much longer and more arduous process.

To sum this section up, standalone houses often give you the option to actively improve the value and rental return of the land and property. This is why most investors who focus on renovations will choose a standalone house.

But this doesn’t mean some active investors won’t renovate townhouses, units or apartments. For instance, there is a strategy focussing on adding an additional bedroom to units, but we typically find this is less common.

Increases in value quickly

Standalone houses are often considered ‘growth properties’, which means they tend to increase in value more quickly.

Many property investors think it’s because the potential for capital growth is in the land. More land = more capital growth.

While that thinking appears to be false, standalone houses have tended to get more capital growth than some other property types.

Why? There are two reasons:

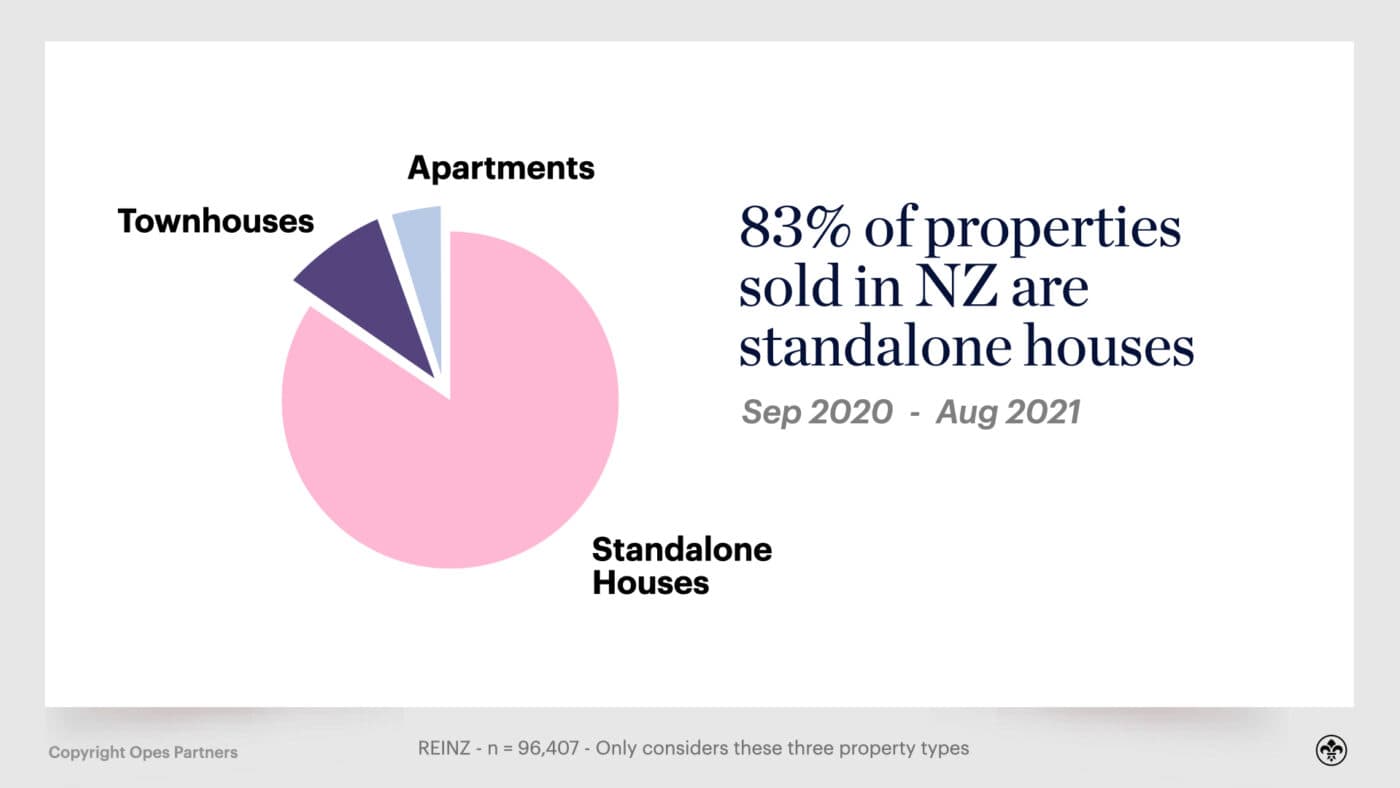

1. Standalone houses are more commonly bought by New Zealanders.

96,407 properties were sold in the 12 months between September 2020 and August 2021.

5% were apartments and 12% were townhouses and units. A whopping 83% of the properties sold were standalone houses.

So, Kiwis tend to purchase more standalone houses and are comfortable doing so.

Admittedly this is a bit self-fulfilling. We have more standalone houses, so we’re comfortable buying and living in them, so we keep buying and living in them.

As our major cities develop and further intensify, we are already seeing groups of New Zealanders happily living in townhouses and apartments.

2. Standalone houses are difficult to substitute for one another.

Ok, we’re getting a bit nerdy here, but stick with us.

Standalone houses tend to be different. Think about the street you live on now. Are all the standalone houses exactly the same? If you live in a subdivision, then maybe. But, if you live on the average New Zealand street, probably not.

Because standalone houses tend to be different, you can’t necessarily substitute one directly for another. This is why owner-occupiers will spend weekend after weekend going to open homes looking for ‘the one’ they fall in love with.

Other types of properties are often less unique. Think about a 100-apartment development.

When you come to sell your apartment, there’s a good chance that a couple of the other apartments in the building are up for sale at the same time.

Those apartments are very near substitutes for your apartment. A potential buyer could buy your apartment, or another owner’s and not be that fussed with the differences.

This is one of the reasons we see standalone houses achieve healthy sale prices. That is especially the case when two owner-occupiers fall in love with the property and emotionally bid the price of the property up.

Easy to sell

Because of the above points, standalone properties are often easy to sell.

Kiwis are used to living in them, and you don’t have direct competition from similar properties.

This is important because at some point, as an investor, you’ll want to exit the market and enjoy the gains you’ve made. Being able to sell the property easily gives you more choice about when and how quickly you are able to access those funds.

More Expensive

If standalone houses come with more land and bigger floorplans, naturally they’re going to be more expensive.

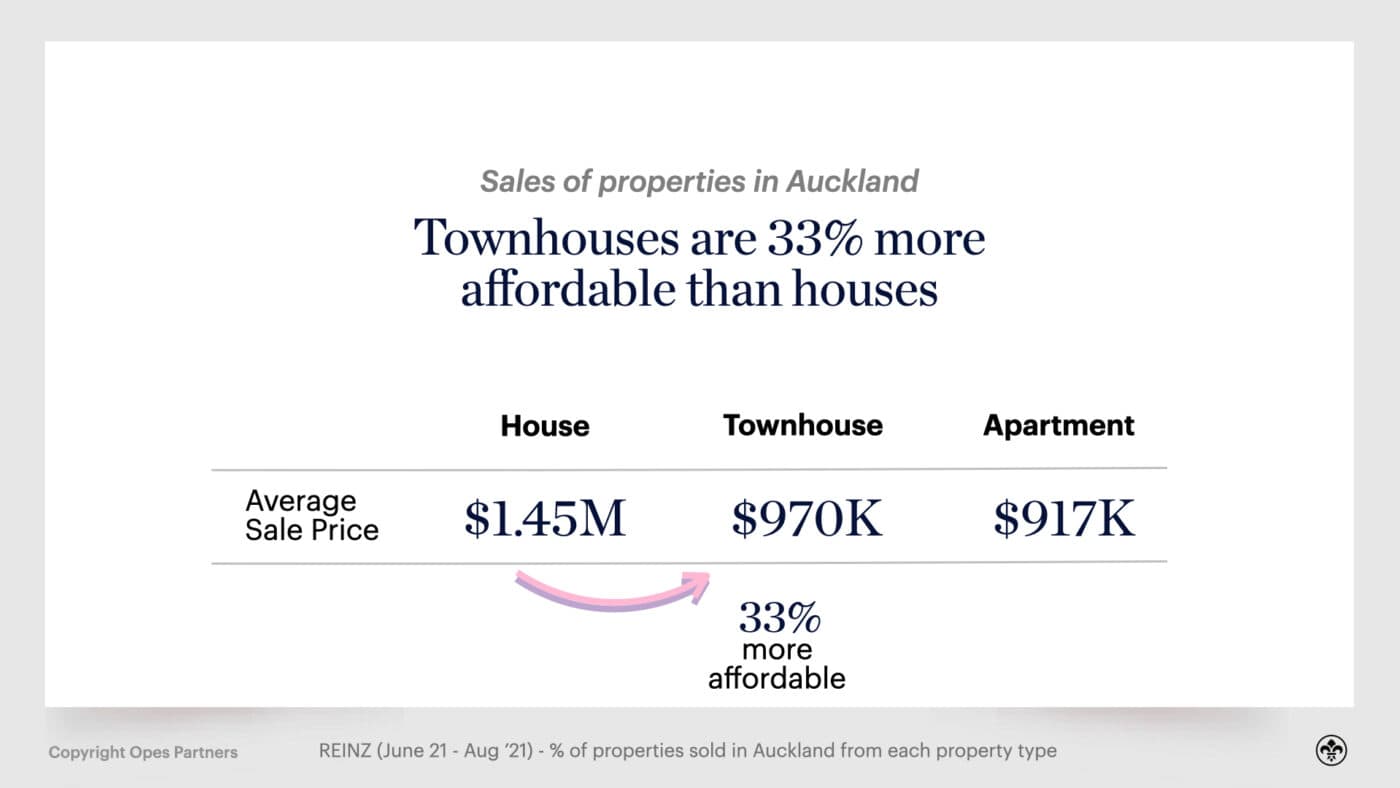

In Auckland, the average sale price of a standalone house was 50% higher than a townhouse/unit, and was 58% higher than an apartment.

Because standalone properties are more expensive, they naturally tend to require a higher deposit. This makes them less accessible for investors who are just starting out and who don’t have as much equity ready to go.

Buying standalone houses also means less diversification. Let’s say you can buy $1.5 million worth of property right now.

On one hand you could buy one standalone house (depending on location).

On the other hand you could potentially buy 2 townhouses, purchasing in different cities and property markets. That spreads your risk more than having your equity tied up in one property.

Lower rental yields

The rental return on a house and land package is not as good as other property types.

This is because, while you might get more rent from a standalone house, the cost to purchase it is so much greater.

Said another way, say you spend 50% more to purchase a standalone house, compared with a townhouse, you often don’t get 50% more rent.

Now, investing in property is all about choices and tradeoffs. So this might be an acceptable tradeoff for you if your strategy is to Buy and Hold over the long term.

But, just be prepared, if you purchase a standalone property it is more likely to have a lower cash return compared to another property type.

If you are purchasing this property with 100% lending (i.e. no cash deposit) then your property is likely to be negatively-geared if you don’t renovate the property to increase the cashflow.

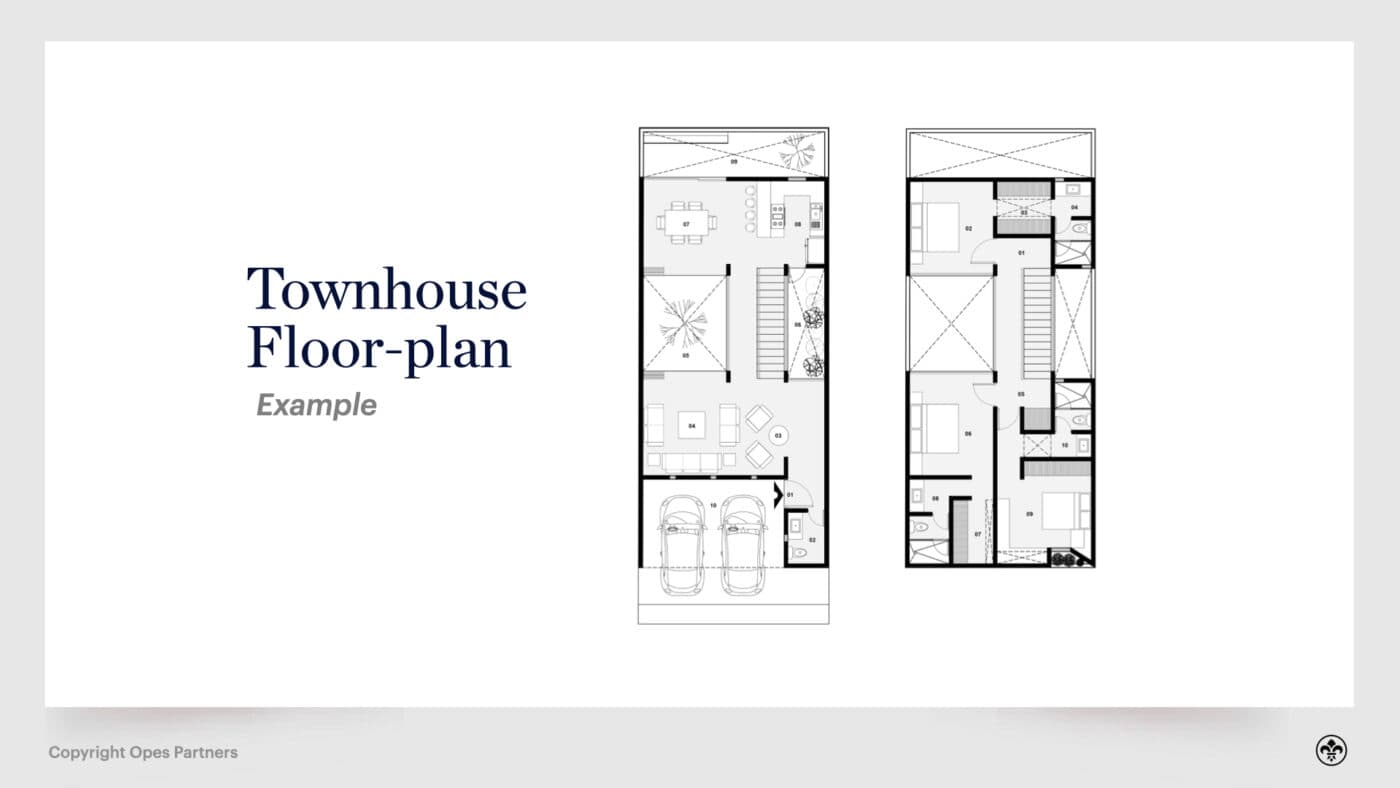

Often, when discussing townhouses, we’re referring to terraced housing.

It’s usually a row of properties attached by at least one wall (if you’re on the end) or joined by two if your townhouse is in the middle.

This is what you commonly see in central areas, and they are your classic developments from Wolfbrook, Williams Corporation and similar other developers.

But, unlike apartments, townhouses come with their individual front doors, either accessible directly from the street or down a shared driveway.

Typically, townhouses are spread over 1 to 3 storeys, have a private patio garden, and often come with an internal garage or off-street car parking.

Townhouse developments can also vary in size, ranging from small, single-digit clusters to large scale neighbourhoods.

But there are other types of townhouses too:

Duplex townhouses. These two attached properties share one wall and are mirrored on either side. These are usually larger homes, maybe 3 or 4 bedrooms over two floors.

- Units. These properties are usually spread over 1 level and sometimes are attached to neighbours.

- Standalone. These are usually single-family homes, most commonly found in large-scale development projects. Standalone townhouses mean you are adjoined to your neighbours' walls, but you will be close to them.

- Townhouses are an attractive way for first home buyers to get on the ladder in central locations and are often purchased by investors.

This is because they are more affordable than standalone houses; new build townhouses come with significant tax benefits and have a reasonable yield and capital growth mix.

Townhouses are a good option for passive buy-and-hold investors. They are very popular among the investors we work with here at Opes Partners.

In fact, 76% of the properties investors bought through us between January – June 2022 were townhouses.

So, let’s go through the benefits of townhouses and who they tend to be the right fit for.

We’ll also talk about the other side of this, which is the drawbacks of townhouses.

Often located in suburbs close to city centres

Townhouses are often built in central suburbs in main cities. Why? Because there is demand for more housing in these suburbs and changing zoning laws have made this possible.

In general, suburbs on the city fringe have tended to get more capital growth than suburbs on the outskirts of the city. So, townhouses are often located in areas that have the potential for healthy capital growth.

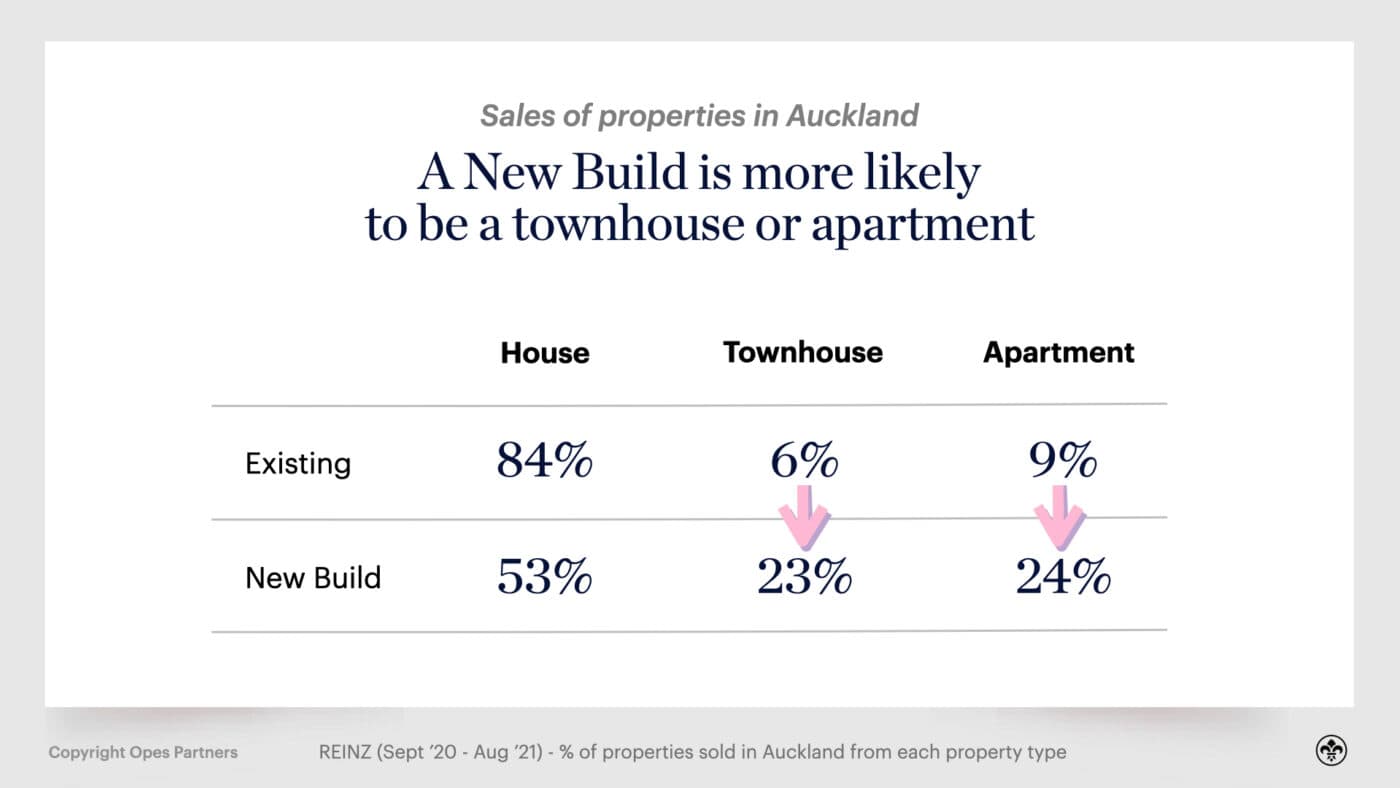

Able to purchase townhouses as New Builds

So far in this guide we’ve mentioned some passive buy-and-hold investors tend to focus on new-builds. That might be because of their lower deposit requirements.

These sorts of investors will often gravitate towards townhouses, since they have become the property of choice for developers to build.

Said another way, there are many more new-build townhouses available to purchase compared with new-build standalone houses.

So, if new-builds are part of your property investment strategy, townhouses are well worth a look.

Townhouses can achieve a good amount of capital gain

Historically, the property investment community has thought standalone houses increase in value faster than townhouses, and townhouses grow in value more quickly than apartments.

The thinking relates directly to the amount of land underneath the property.

Here at Opes Partners we initially thought this too. We stated this as fact in the first version of this guide.

However, what we have actually found when looking at data from CoreLogic is that sometimes townhouses received more capital growth than standalone houses.

Take a look at this table which compares how much more capital growth standalone homes enjoyed compared with townhouses.

If the square is dark blue, then standalone houses got way more growth than townhouses. If the square is light red, the townhouses got slightly more capital growth than standalone houses.

What do we see?

Sometimes townhouses received more capital growth than houses. Sometimes the reverse is true.

Yes, while it’s fair to say there’s a bit more blue in the table than red, which indicates standalone houses got the edge in this data set, it remains untrue to say standalone houses will always increase in value more than townhouses.

Townhouses can achieve a decent rental yield

The rental yield on townhouses tends to fall between that of a standalone house and an apartment.

Primarily, this is down to a mix of the factors already discussed. Townhouses are cheaper than houses, and they’re located in central areas. So, they tend to attract tenants relatively easily.

Lower entry price

Because townhouses are built on smaller plots of land and share walls with neighbouring properties in the development, they can often save on construction costs and are therefore more affordable to purchase.

As mentioned above, in the Auckland market the average sale price of a townhouse was 33% lower than that of a standalone house (June – August 2021).

This makes it easier for first-time investors to purchase townhouses and become property investors.

Now, although we here at Opes Partners are big fans of townhouses, we must also acknowledge the drawbacks.

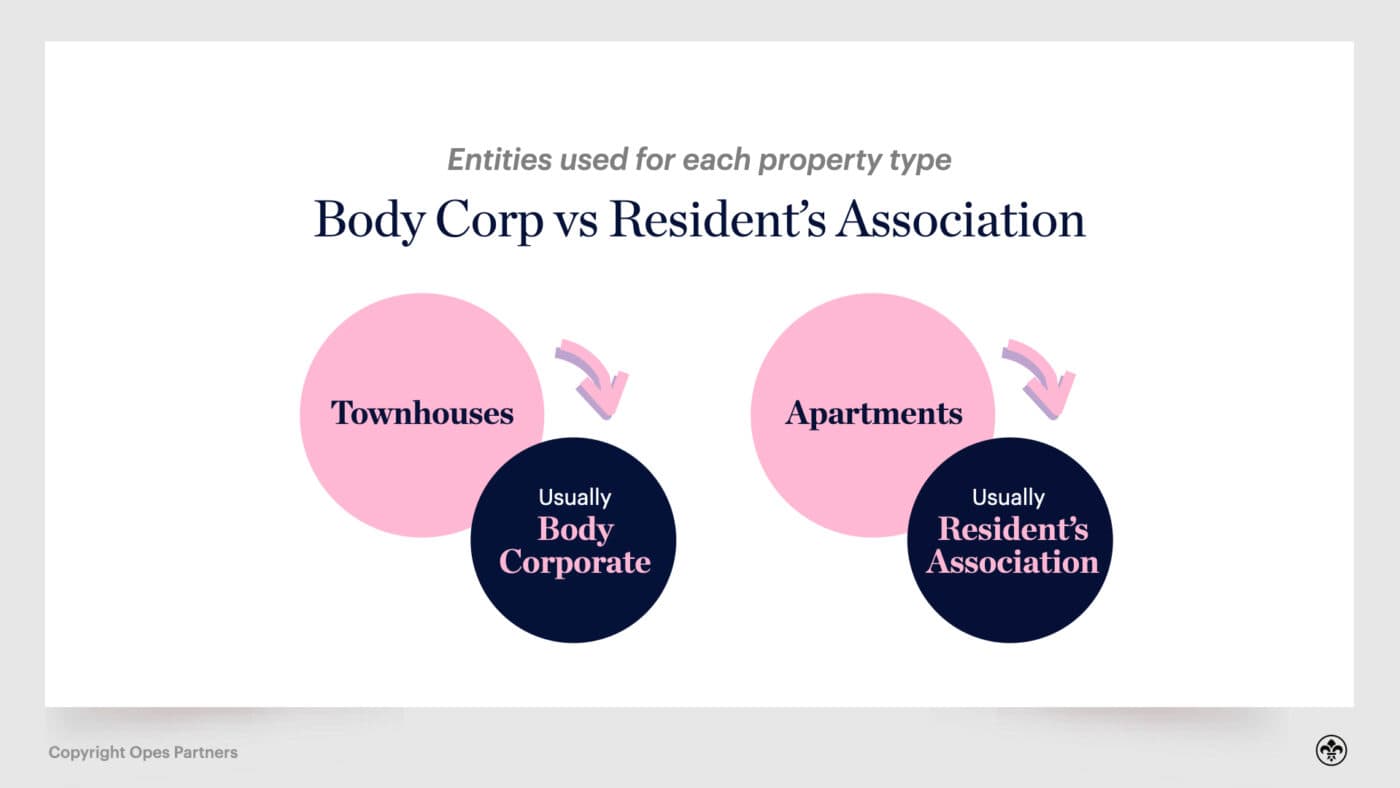

Residents’ association fees

Because your townhouse will share some of the same walls, services, driveways and car parks as the other townhouses within the development, they often come with a residents’ association.

These are essentially lite-body corporates, where you and your fellow owners are bound to follow certain rules. For example, you can’t park a broken down car in your car park.

Membership also incurs a fee to be paid to the organisation. Generally, this is in the region of $500 to $1,000 annually. This pays for the maintenance of any common areas e.g. gardening or the cleaning of shared spaces.

So, this means townhouses (and apartments, which have a body corporate) have an additional expense line compared with standalone houses. Although it is fair to say this is often compensated through higher rental returns.

But say, for example, your property has a pool in the complex and the residents’ association fees are higher, then your rental return may be lower.

Less control over what you can do to the property

If your strategy relies on renovation, then townhouses may be harder for you to crack.

There are a couple of reasons.

To illustrate the first point, let’s use an example to show you why residents’ associations put rules in place about what you can and can’t do.

Let’s say you own a property in a development where all the townhouses are painted black and white.

Then let’s say your neighbour decides to paint their house pink. This messes up the look of the development and might negatively impact the value of your own property.

To avoid this, body corporates and residents’ associations will put rules in place to stop that happening. Other rules can also ensure every property has to have their lawns mowed or state tenants can’t stack empty beer bottles in their windows.

Yes, this all sounds really positive, but the flip side for renovation-focussed investors is that with these associations in place, what you can do to the exterior of your property is limited.

To the second point, because townhouses generally only have a small amount of outdoor living space, it is likely you won’t be able to add on to the townhouse or do any extensive landscaping.

Yes, you can still renovate the interior of the property. In fact, one property investment company solely teaches a renovations-focussed strategy based on improving and figuring the internal floorplan of units.

But your ability to change a townhouse is more limited compared with what you can do with a standalone house.

Finding a tenant for the property for the first time

One final drawback about townhouses investors sometimes worry about is what happens when it comes to tenanting the property.

This is quite specific to new-build townhouse investors. After all, if a whole development of similar properties are purchased by investors, they might all be competing for tenants at the same time.

This can potentially lead to a couple of weeks of your property being empty if you’ve bought in an area that doesn’t have buoyant demand for rental properties.

To combat this, townhouse investors will want to buy in the right area with strong demand for rentals, and might also consider differentiating their property.

For instance, some investors will buy additional appliances (dishwasher, fridge, washing machine) and charge more rent, so their property has a point of difference compared with others in the project.

A townhouse can be a good investment choice for a passive, long term buy and hold investor.

They tend to grow in value well over the long term; they are relatively affordable and usually have a reasonable rental yield.

For example, a 2-bedroom New Build townhouse could be a good fit for investors who are just getting started. For these sorts of investors, affordability is a big drawcard.

However, a townhouse will not be the right fit for every investor.

For example, because townhouses are considered a growth-focussed investment, they won’t be the right fit for investors who really need yield.

Those tend to be investors who are close to retirement or already have significant assets and are ready to live off the rental income from their portfolios.

In that case, higher-yielding investments like dual-key apartments are likely a better fit.

Similarly, if you are a renovations-focused investor, townhouses might not be the right for you. The reason is that renovations-investors often add bedrooms to a property, which is easier to do with a standalone house than with a townhouse.

Finally, some investors can’t get their heads around townhouses and only want to invest in standalone houses.

Look, if a townhouse will cause you to lose sleep at night, then it’s probably not the right fit for you.

Apartments are separate residences within one conjoined building.

Buying an apartment means you typically share the whole building and its common areas with other owners or tenants within the building.

With apartments you typically have neighbours on either side of your unit and you’ll often have homes above and below you too.

Apartment buildings can be large or small, but the key difference between an apartment and other property types is that there are multiple units stacked on top of one another.

Most apartments also share common areas, such as an underground car park, a lobby, and perhaps even common courtyards. This may also include a shared elevator, or even amenities such as a pool or a gym.

Because there are shared spaces, apartments also have a Body Corporate. This is an entity that governs the building.

A committee is typically elected from the owners of the units and each owner pays a share of the maintenance. Some owners pay more than others, depending on the type of apartment they own.

Not all apartments are the same. There tends to be 3 main types in New Zealand.

Standard apartment

This is the most common apartment. It’s a single unit within a building that contains many units. There will likely be other units on the same floor as you, and you may use an elevator to get to your floor.

Walk-ups

“Walk-ups” are a fancy way of saying an apartment with no lift. These are commonly found in New York. And because there isn’t a lift these apartment blocks tend to have fewer floors.

In addition, instead of a bunch of separate units being housed on the same floor, your apartment may have the whole floor to itself.

Walk-ups still have people above or below, but generally there is no shared elevator. This means you walk up the stairs to the apartment, hence the name.

Walk-ups were a feature in Hobsonville Point, Auckland.

Dual keys

Dual keys are a type of multi-income property.

Instead of having a single unit, a dual key has two separate, but adjoining, units held under one legal title.

So, from a tenant’s or home buyer’s perspective, the two apartments feel separate but legally they are the same property.

Again, this type of apartment is a new concept in New Zealand but is well established in some Asian countries.

Here’s a floor plan example from a development in Ellerslie, Auckland.

In the above example the size of the property is the same as a standard 2-bedroom apartment (75sqm). However, it is configured as a 1-bedroom and a studio.

For a property investor that means the two units can be rented separately to two different households under separate tenancy agreements. This means you can have two sources of income, which maximises your rental yield.

For instance, let’s take another look at Safari Group’s dual-key apartment in Ellerslie.

The rent was expected to be $515 for the one-bedroom, and $480 for the studio. That’s $995 of income per week. Based on the purchase price of $915,000, the property would generate a 5.7% gross yield.

From the tenant’s perspective, apart from a shared entrance way, they are totally separate.

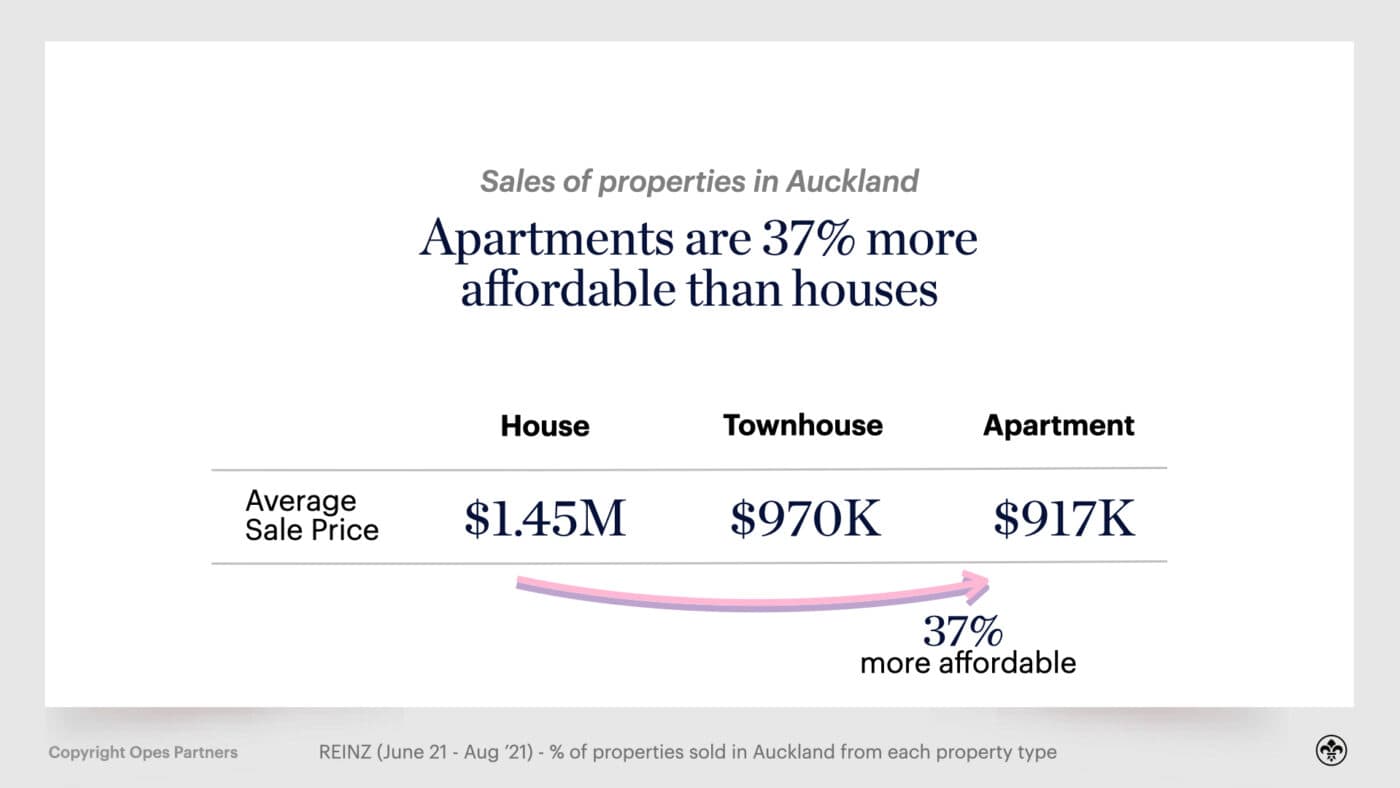

Cheaper entry price

The average sale price of an Auckland apartment (June – August 2021) was 37% lower than a standalone house in the city.

So apartments can be a good option for investors who have a lower deposit, but who are still keen to get a foothold in the market.

Higher yields

Because apartments are relatively cheaper to purchase, while still attracting good rents, they tend to have higher yields.

This means they are more likely to be cashflow positive compared with other property types.

Because apartments are high yielding, they are a good option for investors who are nearing retirement and are more interested in cash now, rather than long-term gains in the value of their property.

Very low maintenance

The vast majority of apartments have a unit title. This means you collectively own the land underneath the building with all the other owners within the development.

Because of this, you legally need to have a body corporate to manage the joint areas and set rules.

While this carries an extra cost (more on this below), it also means you don’t have to worry about the maintenance of the exterior of the building or any landscaping.

Instead, the body corporate will take care of this on your behalf. This means apartments often have a few less headaches than the likes of a standalone house.

Slower capital growth

Although apartments have higher yields, their values tend to grow at a slower rate.

For instance, take a look at 2-bedroom properties between the year 2000 and 2020.

A 2-bedroom apartment grew in value significantly slower than standalone houses.

When we run the numbers on a potential purchase here at Opes Partners, we often use 3-4% as an estimated annual capital growth rate for apartments. Comparatively, we’ll typically use 5-6% for townhouses and standalone houses.

Body corporate fees

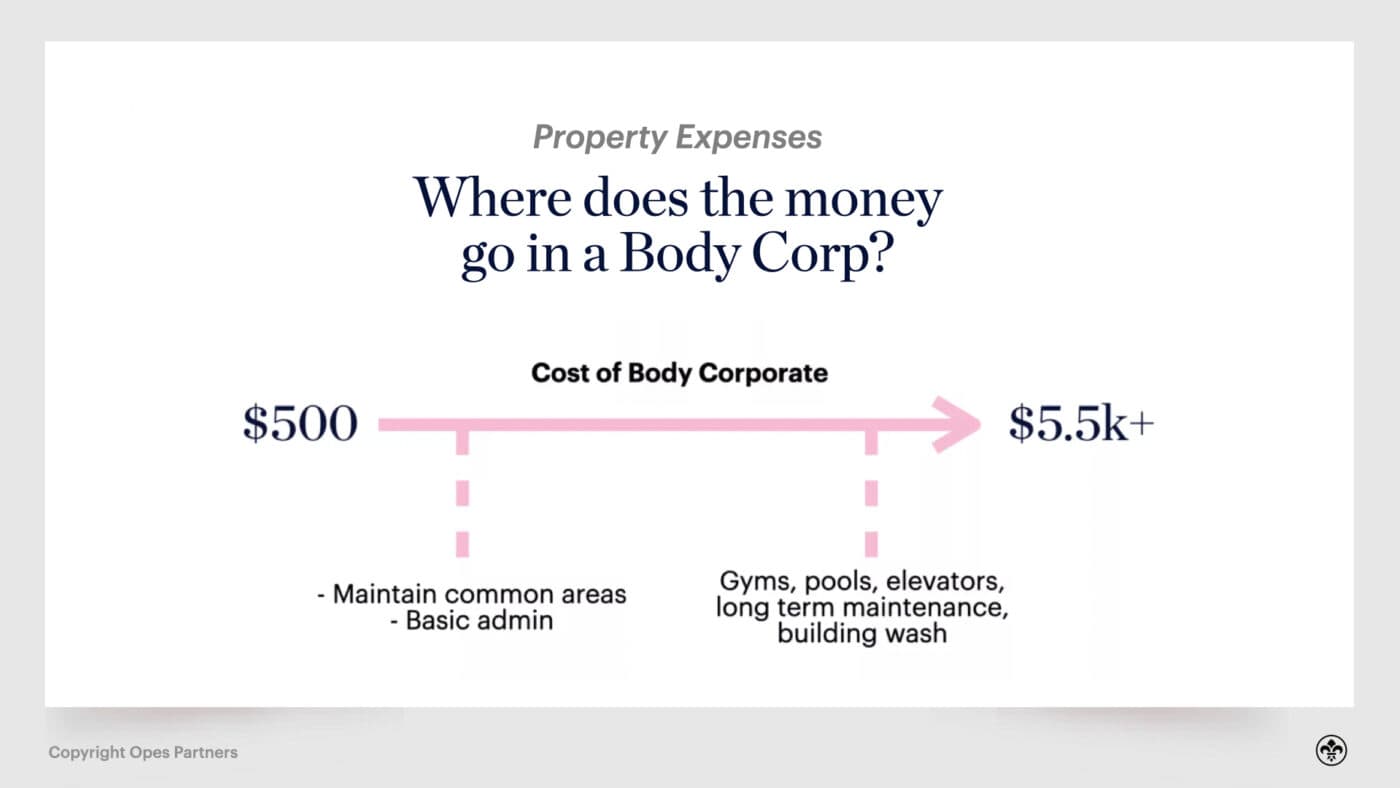

Since apartments usually have unit titles, they legally need to have a body corporate.

The fees body corporates charge can be uneconomically high for property investors.

If a building has lots of services, like pools, elevators, gyms or an onsite concierge service, the costs to run these services will be passed on through higher body corporate fees.

This can be a drawback, especially if those fees are high, and the additional rent you get from having these services is relatively small.

Less control over what you can do to the property

Because you are unable to alter the outside of the property, through landscaping or painting the property (think about it, you couldn’t paint the outside of just your apartment), there are a smaller number of ways to add value to the property.

This makes apartments less attractive for investors who are focused on renovation.

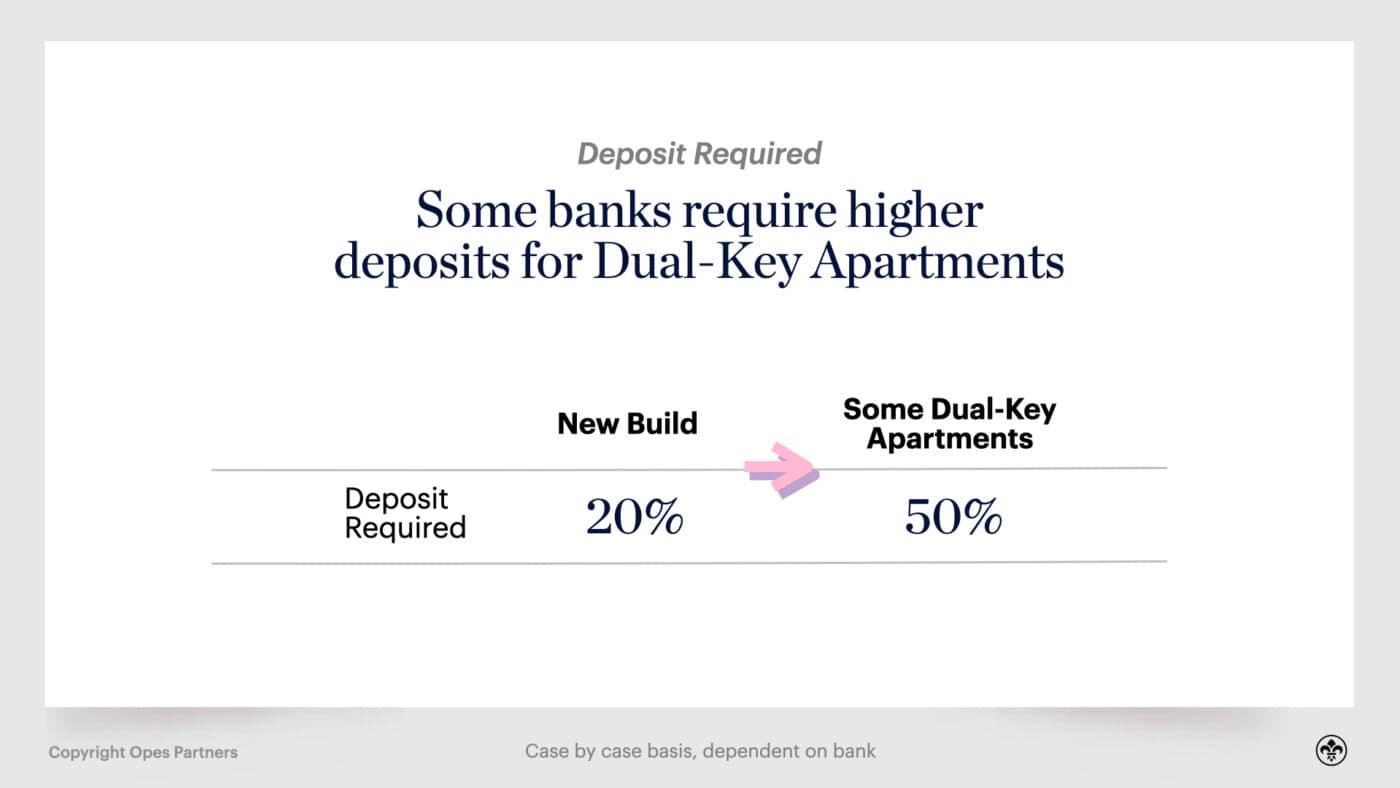

May need a larger deposit

Sometimes the bank will require an investor to have a larger deposit to get lending for a small or unusual apartment.

Although banks will usually require a 20% deposit to buy a new-build property, we have seen instances where the bank has required a 50% deposit.

This is usually if the apartment is small – less than 55 square metres in some cases – or if the apartment is a dual key.

The reason for this is these properties have a more limited market. So if you defaulted on your mortgage and the bank needed to sell the property quickly, they may need to do so at a large discount.

Because of this they want a bigger buffer between the price of the property and the mortgage they lend you.

All things considered, apartments can be a good investment for some investors, but they aren’t the right fit for everyone.

Apartments can be a more affordable entry point into the market for first time investors, and their location in city centres can mean successfully buying in an area you might otherwise be locked out of.

So this can make them an option for first home buyers, or investors on a limited budget.

And while apartments aren’t generally considered growth properties, they can partially make up for it in higher yields.

That can make them a good fit for investors who are nearing retirement and want to earn a passive income from their properties.

They can also be a good fit for investors wanting to complete a Wealth Wheel.

But they aren’t being built everywhere.

For example, if you are looking to invest outside Auckland or Wellington it is unlikely that an apartment will be the right fit for you.

When we talk about land in this context, we are talking about undeveloped land that has nothing on it – a blank site. Investors who purchase this sort of property are often known as land bankers if they sit on it and don’t develop it immediately.

Goes up in value the quickest

Bare land tends to go up in value quickly because developers want it.

If house prices are increasing at a rate faster than the cost of building the house, then developer margins start to increase. In other words, building properties becomes more profitable.

Because of this, developers can bid the price of land up, and there’ll generally be more demand for it.

So in a rising market, the value of bare land can increase quickly.

Lots of opportunities to add value

If you choose to build on the land yourself (i.e. you become a developer), you can add a lot of value to the property very, very quickly.

Adding a house will add hundreds of thousands of dollars to the value of the property. There’s lots of risk associated with this strategy, which we’ll get into, but the rewards are certainly there.

Lowest stress while you hold

If you invest in land, and don’t develop it, there are no tenants and no real maintenance that needs doing.

This means holding the land is very low stress while you’re doing nothing with it.

No Cashflow

Because you can’t rent out land (generally) to residential tenants, if you invest in land and don’t develop it, you probably won’t have any cashflow.

This makes it much harder for everyday New Zealanders to invest in land because they’d have to service the mortgage for the land out of their own income.

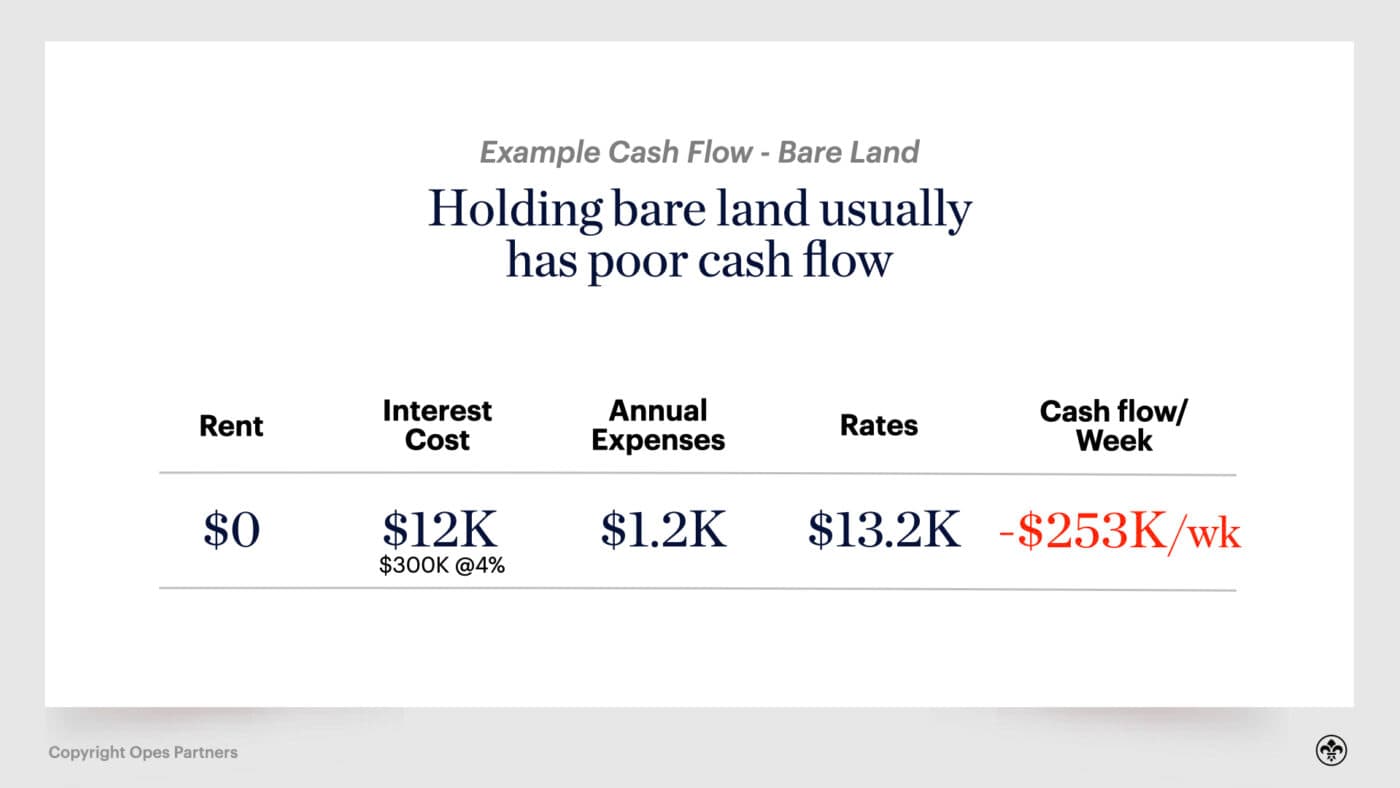

For instance, let’s say you invest in a $300,000 piece of land. You use a 100% mortgage to purchase the land at a 4% interest rate. That means you will have annual interest expenses of $12,000. In addition, you might have rates of $1,200 a year.

This means you have total expenses of $13,200 per year or $253 per week, which you would have to pay yourself.

Many New Zealanders probably couldn’t afford to pay this. And let’s be honest, a $300k piece of land is cheap. If you’re buying in the main centres the section will be more expensive.

Big downside if you choose wrongly

There is a big financial downside if you choose the wrong piece of land. Because you’ll potentially have large outgoings each week, you’ll rely on the land to go up in value quickly. So, what if it doesn’t?

Say you have the decision to either invest in a standalone house or a piece of land.

The investor contribution you have to make to the piece of land each week, as we said, is $253 per week ($13,200 annually).

Let’s say the alternative is to purchase a standalone house that is negatively-geared (i.e. the rent doesn’t cover all the expenses) by $50 a week ($2,600 annually).

The next way to break down properties is by their ability to increase in value, compared to their rental return.

This means the piece of land has to go up in value by at least an extra $10,000 per year (compared to the standalone property) for the land to be the better investment.

High cost if you choose to build

If you do choose to go down the development route, you will need a lot more capital in order to build on the land.

Building a house means taking on six figures of additional debt and, most importantly, a lot more risk and stress as you build.

This section is way shorter than it could be, or some would say should be, But the point isn’t to tell you which is better.

Instead, the purpose is to give you an appreciation for the differences in property types, and who they tend to be the right fit for.

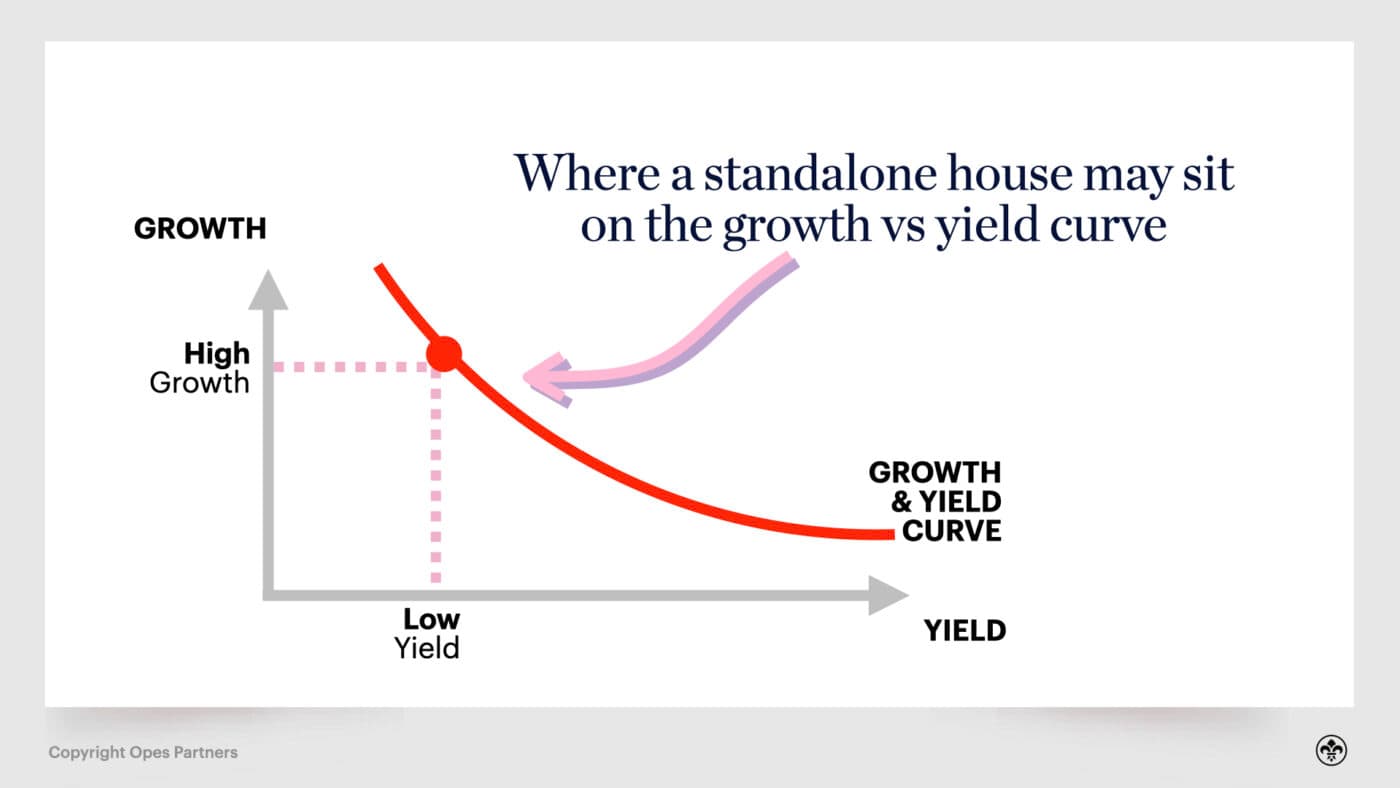

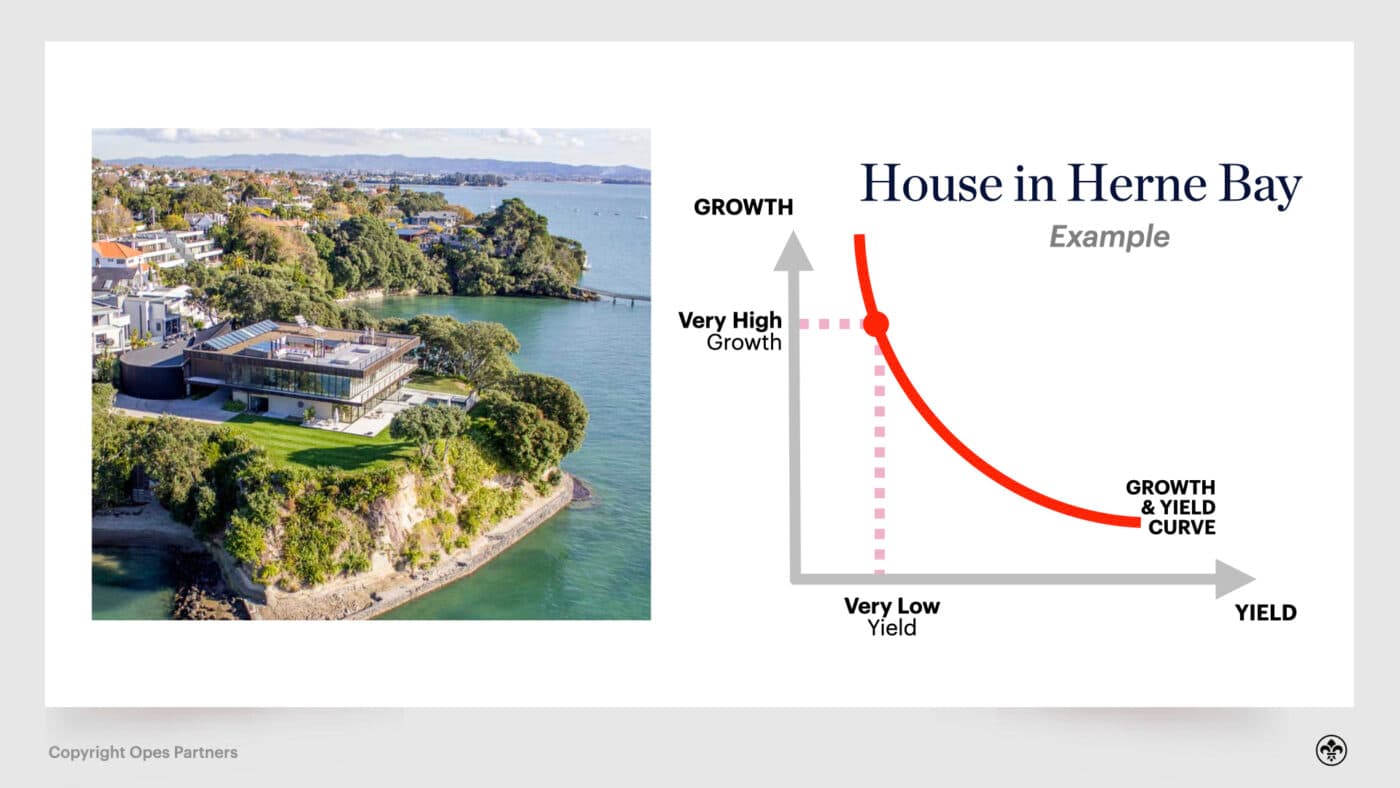

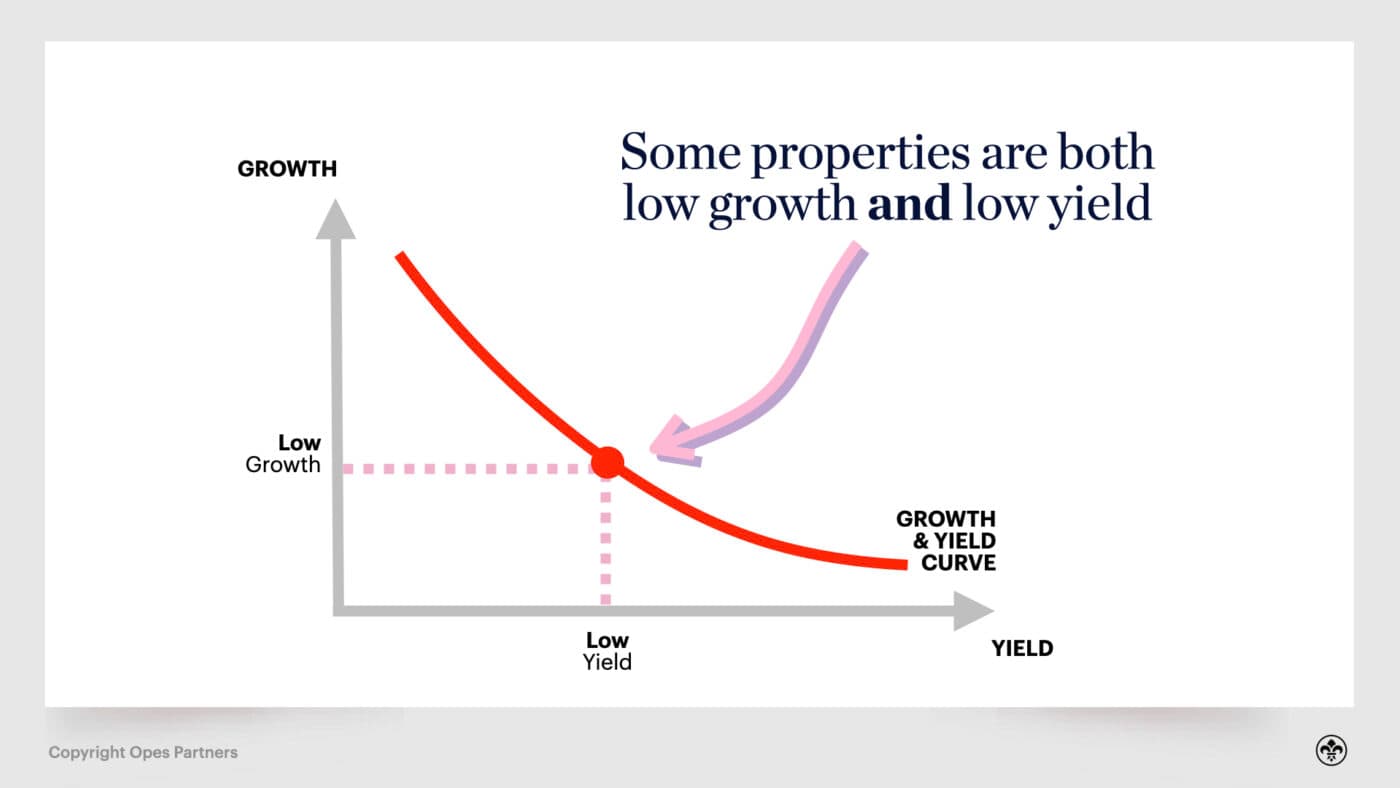

If you’re following a passive buy-and-hold strategy, there is often a trade-off between the two.

This means you’ll either have a higher growth property (which earns a lower amount of rental return) or you’ll have a higher yield property (which achieves a lower rate of capital growth).

This is because higher yield properties are often specifically configured to increase the rent they achieve. But in doing so, this can blunt their attractiveness to owner-occupiers, who tend to bid up house prices if they are emotionally attached to a property.

Let’s dive into some examples to show you what we mean.

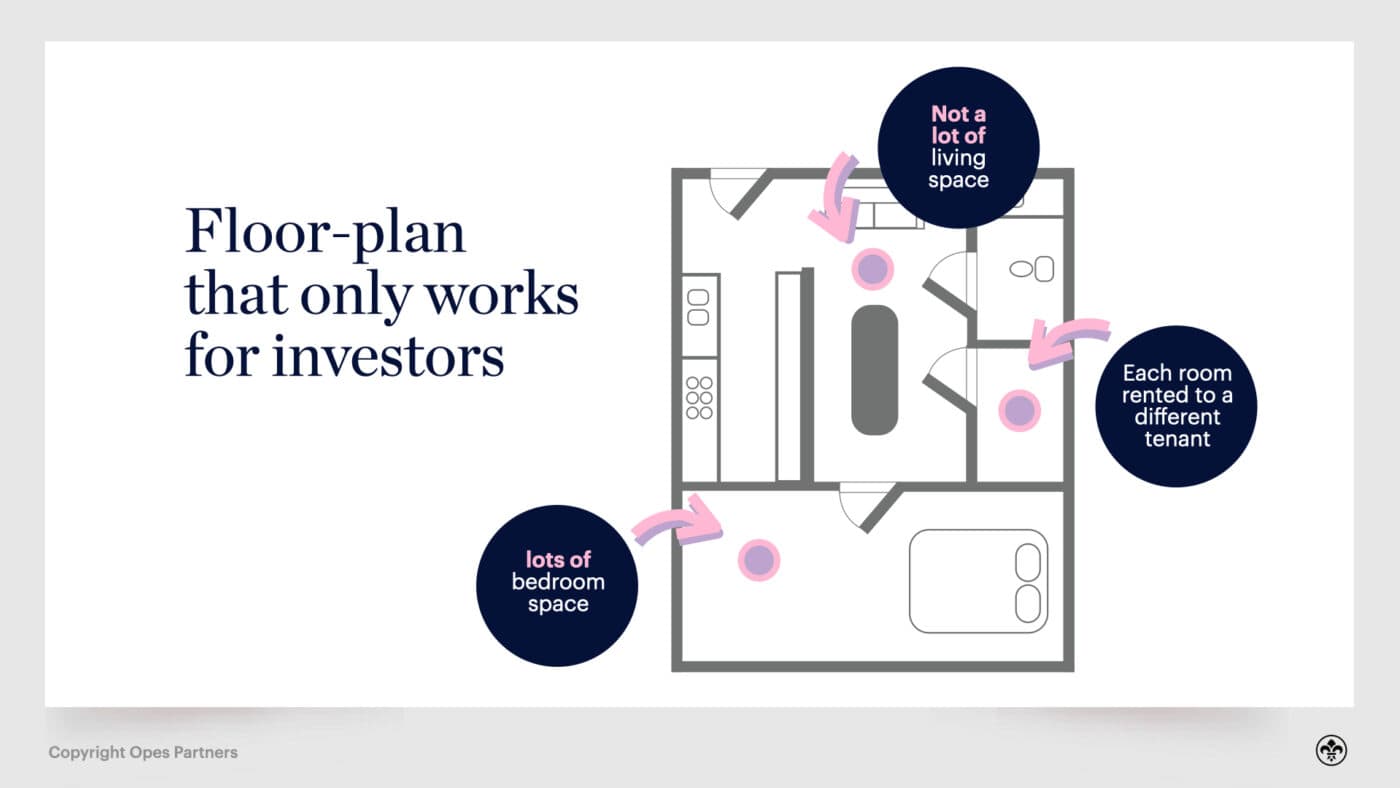

Here’s an example of a high-yielding property based in Hamilton. The townhouse contains 4 separate studio apartments, with a small kitchen and lounge area.

Each studio apartment has its own ensuite, decent sized bedroom and a kitchenette.

This property has been configured for mature students or for hospital workers who spend a couple of days a week in Hamilton.

At the time of development, the estimated rent per room was $250 a week each, and the property was sold for $729,000. This property has a gross yield of 7.13%, which is a very high yielding property for a new-build.

How? Because each room can be rented separately, the investor is able to get a much higher rental return than would otherwise be the case.

But, of course, when the investor wants to sell the property, who is going to buy it?

It won’t be an owner-occupier wanting to shift their family in.

Why? Because in this property the living areas (dining rooms, kitchen, lounges) have been sacrificed for more bedroom space, which makes sense because of the target tenants (mature students or professionals who live alone).